This is where I drove my go-cart, Crosby Doe says, turning his champagne-colored Jag down Pasadena’s Hillcrest Avenue on a rolling tour of the posh Oak Knoll district where he grew up. A civilized gent in a stylish blend of creams and browns, Doe points to a series of houses, fondly recalling memories of each. There’s the wood-shingled Blacker House, an Arts & Crafts masterpiece designed by Greene & Greene, where he voted for the first time in 1972. Across the way, there’s an unusual stucco Greene and Greene that has a basement-level ballroom where he used to put on plays with the other kids. Around the corner, on Wentworth, there’s an eclectic two-story by Pasadena architect J.J. Blick that reflects both Mission Revival and Craftsman elements. And just down the block is his own childhood home, a 1923 traditional with four bedrooms that his stockbroker father bought for $28,500 in 1957 (it was on the market for $1.6 million last year). These houses evoke the past for Doe, but also embody his life’s work. “Every house here has integrity. And they’ve never changed. I know I’m going to be dead,” says the 52-year-old realtor, “and these houses will still be great.”

The same cannot be said for much of the structural mediocrity littering Los Angeles today. But as a real estate broker who recognizes the value of preserving architectural history, Doe has made a career of matching buyers who care about houses with integrity to the historic and modernist works of architecture icons such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Rudolf Schindler, Harwell Hamilton Harris, Gregory Ain, Ladd & Kelsey, Barry Moffitt, John Lautner, J.R. Davidson and Pierre Koenig.

These homes aren’t for everyone, and Doe knows it. Some of them, like Wallace Neff’s Shell House or Bruce Goff’s Al Struckus House, both of which he sold fairly recently, are even oddball gems that require just the right kind of esoteric appreciation-not to mention TLC.

That’s why Doe’s involvement with the houses he sells doesn’t end when escrow closes. As self-appointed tastemaker-historian, he often takes it upon himself to tell people when he thinks they’re making a mistake. “I’ll say, `Please leave this,’ or, `It’s okay to take that out,'” he admits. “Buyers have to work within the spirit of the house.”

Some might ask how a realtor can get away with being a design arbiter or wonder who deemed him the decor police, but Doe’s sense of urgency springs from experience. Over his 25-year career–currently as a partner in the Beverly Hills-based Crosby Doe Associates —he’s seen too many houses lost or cannibalized. He can list the names of those that were “modernized” in the ’50s with such “improvements” as louvered windows and wall-to-wall carpeting, from Irving Gill’s Dodge House in West Hollywood to the great Spanish-style houses by Wallace Neff and Roland Coate. But for Doe, the most galling example of misguided renovation occurred during Madonna’s ownership of John DeLario’s 1926 Hollywood Hills masterpiece, Castillo del Lago.

Once his favorite property in L.A., one he’d sold three times before, Castillo was transformed by the pop singer (and her designer brother, Christopher Ciccone) from a grand Andalusian Spanish house into a root-beer-red faux Florentine villa. Even worse, Doe has to see it every day; he and his wife Linda live in a painstakingly restored two-story Spanish aerie designed by Blick on the same mountaintop. “She wrecked it,” says Doe. “They took the historic tiles off the roof, threw them in a Dumpster and put on these Taco Bell tiles. It was one desecration after another. Criminal!”

Doe’s outspokenness about the city’s architectural treasures has earned him some critics-especially among his colleagues. “Aggressive purism can be quite unattractive,” sniffs one broker. Others agree that Doe can sometimes be difficult and didactic.

“I probably pissed off Diane Keaton with my opinions,” admits Doe, referring to comments he made about the ultra-contemporary interior Josh Schweitzer designed for the Novarro House. A Lloyd Wright classic in Los Feliz originally built for silent film legend Ramon Novarro in 1928, it was sold by MD&D to a string of owners (including restaurateur Michael Chow) before Keaton bought and renovated it in 1988 (she has since moved to a Spanish-style Wallace Neff in Beverly Hills). “I may have mentioned,” he concedes, “that I thought this was atrocious and Eric Wright [the architect’s son] would have been a better choice.”

But his strong opinions have also earned Doe a coterie of devotees. They know he’s been in this game longer than anyone in L.A.–he sold his first architecturally significant house, a Neutra, in 1973–and many rely on his guidance.

Take actress Kelly Lynch and her screenwriter husband Mitch Glazer. Thanks to Doe’s instincts, they were able to nab a 1950 John Lautner fixer-upper in Los Feliz from under competitor Leonardo DiCaprio’s nose last May. Doe urged them to up their closed bid by $20,000, and a disappointed DiCaprio lost out on a rare example of mid-century architecture.

The first time they saw the neglected residence, “there was so much stuff going on, you could get vertigo,” says Glazer. “But Crosby was a calming voice, saying, `Don’t worry, there are plans for restoring this thing.'” Soon they had so many workers traipsing across the house’s slate-floored living room that the circular wood-and-glass structure resembled an archaeological dig. Lynch and Glazer are presently stripping away additions in an effort to restore the house to its original design.

Doe applauds their ambition. “Ever since that house was built, it’s gone downhill from Lautner’s concept–one of the most exciting in the city,” he says. “By the time Kelly and Mitch came, it had horrible additions, tract-house cabinetry–it was awful.” Doe ranks the couple as “my best clients for restoration since Joel Silver.” (The film producer bought Frank Lloyd Wright’s Storer House near Laurel Canyon from Doe for $725,000 in 1984; it’s now listed with Nourmand & Associates for $5.5 million.)

Lynch and Glazer also own a sleek Neutra that was built in 1960 at the foot of Mount Whitney in the craggy outpost of Lone Pine, California, which they bought through Doe more than five years ago. Says Glazer, “When we were putting the Neutra house together, he called and said, `You know, there’s a great grasshopper chair that I saw in [the shop] Skank World’–which we went and got immediately. And it was perfect. What real estate man would say that? He’s got real opinions and amazing taste coupled with incredible knowledge.”

Today, Lynch and Glazer laugh about the first time they met the broker at their rented California ranch house in Santa Monica. Most of their friends admired the property for its ’60s-vintage Doris Day-Rock Hudson appeal, but Doe pronounced it “vin ordinaire.” “He’s so thorny about what he likes or doesn’t like,” says Glazer. “We both found it refreshing.”

Though Hollywood types now make up a large part of the clientele for modernist houses, it wasn’t always that way. Many of the architects who built them were European émigrés who brought the international style of modern architecture to L.A. At their best, these homes offered visionary alternatives for living, creating greater unity between interior and exterior space–something that suited the city’s climate and terrain. Early owners included teachers, psychologists, artists–intellectuals and liberal thinkers of often modest means.

Yet by the ’70s, the escalating real estate market had made these houses treasures for the elite. And lately, style setters in fashion, art, music and movies have taken notice. Suddenly, in smart circles, names like Neutra and Schindler have become as familiar as Prada and Gucci. Director David Lynch bought a flamboyant Lloyd Wright; fashion designer Tom Ford is restoring a Neutra in Bel-Air; photographers such as Dewey Nicks like to use modernist settings for magazine shoots; and movies such as L.A. Confidential (which features Neutra’s monumental 1929 Lovell House) and Playing by Heart (which features Pierre Koenig’s 1959 Case Study House No. 22) have made them a resonant part of the contemporary L.A. landscape.

Now the rage for modernist architecture is trickling down. As the millennium closes its value has been upped among young buyers seeking something of 20th-century style and substance. Unfortunately, there are only so many to go around–among M&D’s inventory of about 2,000 architecturally significant houses in the L.A. area (not including Palm Springs, Montecito and parts of Pasadena and Palos Verdes), there are only 95 Neutras, 65 Schindlers and 39 Lautners.

In 1995, a three-bedroom Neutra in the hills sold for $450,000. “Today, conservatively, I could sell it for about $800,000,” says Doe.

A Lautner (the Carling House) that he sold to television ad director Steve Ramser in May 1997 went for double what the previous owner (who restored it) had paid for it in the late ’80s. The demand for such houses has prompted competitors to beef up their presence in this specialized arena: Jan Eric Horn, a former M&D agent, launched an architectural properties division for Coldwell Banker several years ago. But some believe it’s Crosby Doe that sets the aesthetic standard — its weekly one-page L.A. Times ad defines the firm’s mission state — with one prominent word: ARCHITECTURE.

“Fortunately, through our marketing, most of the people who come because it’s a Neutra home are not going to wreck it,” says Doe. When the realtor recently sold a Neutra in the Valley to buyers who loved the square footage more than the architecture, he educated them. “We gave them books, showed the importance of how carefully the house was built. They have the original drawings where Neutra specified the quality of paint, the material. He wrote a book on every one of his houses.

“Unfortunately,” he admits, “I probably lose business because buyers aren’t patient enough to wait [till there’s something good]. If there’s a cost to just wanting to sell the best, it’s that I’m not selling the most. I’m not a big, big broker who is selling $80 million worth of property a year.”

“I think Crosby has a rather unique understanding of good architecture,” says Julius Shulman, the 88-year-old godfather of architectural photography, who has known Doe since he hung his first FOR SALE sign. “The others are salespeople. They’ re serious and good to their clients, but he’s a real specialist.”

Even competitors concede that Doe’s knowledge is indisputable. “You need an eye in this business,” says Barry Sloane, who heads Fred Sands’s architectural and historic property division in Beverly Hills and who bought two homes from Doe before he started in real estate. “I’ve got an eye. Crosby’s got an eye. A lot of people don’t. There are probably six or seven brokers who I call about architecture. That’s all, maybe less.”

When he started in the business 25 years ago, Crosby DeCarteret Doe was the last to expect that someday he’d be dishing out architectural advice. But he was always railing against the ordinary. He dropped out of the marketing program at the University of Colorado in Boulder, he says, because it “catered to such a low common denominator.” It was the late ’60s, and his years in Boulder were a radical departure from his privileged Pasadena upbringing. Returning home in 1970, he worked various jobs, including a turn as an orderly at a mental institution. Then in 1973, when his father was “throwing his hands up” about his hippie son to a fellow boat owner in Marina del Rey named Larry O’Rourke, O’Rourke gave Crosby a job in his Hollywood real estate office. Ironically, Doe’s father had once likened realtors to “used car salesmen.”

“I had no expectations,” says Doe. “My goal was: Get your first listing, get your first sale. I was fortunate to knock on the right door–one of the first listings I had was an original Neutra house.” Almost simultaneously, he ran across a pocketsize bible called A Guide to Architecture in Southern California. Printed by the L.A. County Museum of Art in 1965, it was filled with street maps and black-and-white photos of architecturally significant homes. “When I saw that, everything clicked,” Doe says. “The whole career was before me. There was this entire inventory of merchandise that no one had paid attention to as a special market.”

Though some brokers were already selling ‘architecture,’ they weren’t serious about the concept. “We wanted to do something unique in the market,” says O’Rourke, now based in Newport Beach. “But Crosby jumped on the bandwagon and made architecture his specialty.”

When the real estate market dropped 40 percent in the early ’90s, architectural homes took a 20 percent loss, Doe estimates. But more recently, as the market has returned to its apex, significant architecture has topped it. “I think it will stay strong and appreciate through the spring,” says Doe. “As long as interest rates hover around seven, I think it’s still very healthy–especially in Hollywood.”

Still, he worries about new dangers: “The demand [for architectural homes] is driving up prices, and sellers are taking advantage, forcing realtors into pushing the market.” Just getting the listing, he says, is becoming “almost an auction. So the pressure among brokers is to put everything at top value.”

If a broker is too sensible, however, he’ll lose the listing. That’s what happened when Doe was first asked about representing Bruce Goff’s Struckus House in Woodland Hills. “I knew the original owner, and after he died, I met with the daughter, who really loved the house.” After Doe told her what he thought it would sell for (a figure much lower than she had anticipated), “she didn’t ever want to talk to me again,” he says. In the hands of local brokers, it languished on the market for years.

Enter Ann and Kevin Marshall, a couple who work at the Getty Center. Ann, a former architect in Indiana, appreciated Goff’s unique “organic” architecture (this is the only residence in the area by Goff, who is best known in California for designing the L.A. County Museum of Art’s Japanese Pavilion). When the 1,730-square-foot home was being built in 1983, one newspaper nicknamed it the “Cyclops Silo” because of its porthole windows (actually vertical domed skylights) that peer out from tribal redwood walls under a Popsicle stick-beamed roof. “It’s like living in a sculpture,” says Kevin.

“When the Marshalls came along, I had my golden opportunity,” says Doe, who represented the buyers. “It’s a wonderful house, and these people love it.”

Though the house’s asking price had dropped substantially from its original listing down to $334,900, and the Marshalls got it for less than that, it was still “one of the most challenging houses” Doe ever helped get financed.

“Savings and loans and banks are mass marketers. Their appraisal system doesn’t work at all for architecture,” gripes Doe. “To banks, a house is just so many square feet, whether it’s Frank Lloyd Wright or Richard Neutra. If you have a paint-by-number painting or a Picasso, the way they would decide how much it’s worth is to measure the square inches and the amount of paint on it.”

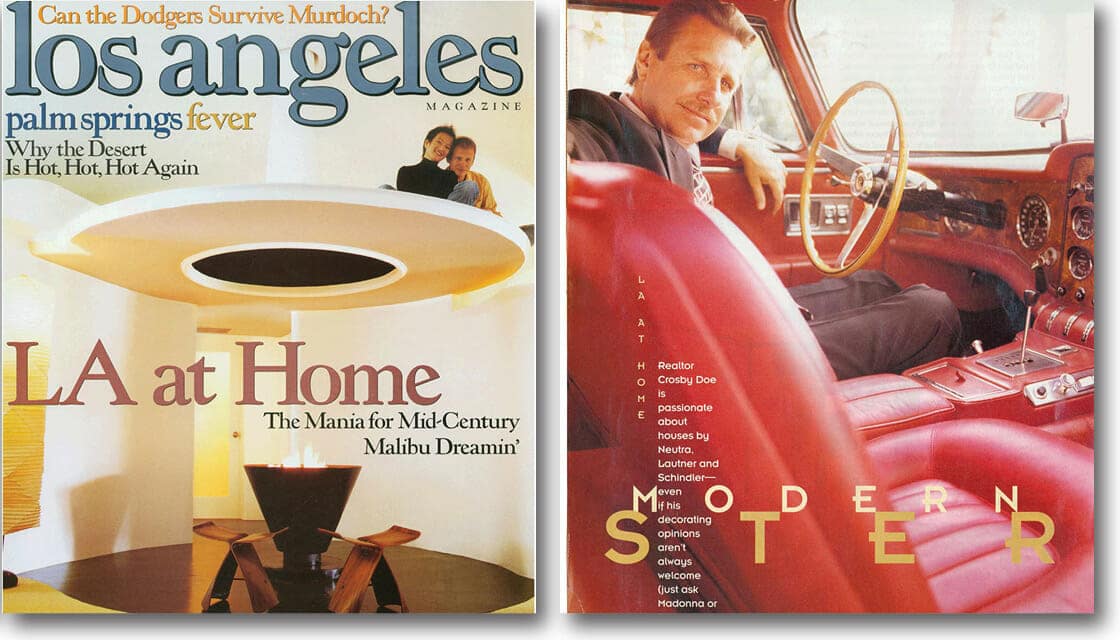

Another house that banks probably don’t quite get is the Shell House (featured on the cover), situated on a quiet corner a few blocks from Oak Knoll, where Doe grew up. When Doe used to pass the flying saucer-shaped structure on his way to grade school, he had no idea it would someday be regarded as an architectural classic. A ’40s Wallace Neff-designed “experiment,” it was meant as an alternative to the showplaces Neff built for A-list clients like Charlie Chaplin and Cary Grant. Named for the nautilus seashell that inspired it, it was created by covering a giant shell-shaped Goodyear balloon in gunite (a concrete mixture sprayed over steel), then collapsing the balloon. Neff built it for his brother, and it was the architect’s own final residence prior to his death in 1982. From the curb, Doe surveys Neff’s last stand with proprietary eyes. “It isn’t a big house,” he says, “but it’s major.”

Doe is greeted warmly at the front door by the house’s new owner, Steve Roden, who was living in a Park La Brea tower apartment with his wife Sari when he saw the house listed by M&D. “I’d been watching their ads and wanting to call Crosby for so long,” says Roden (who grew up in a 1948 Schindler in Studio City).

When the 34-year-old artist first saw the Shell House, “I lost my mind,” he says. “The minute I opened the front door, I wanted to move in. It’s the most interesting house I’ve ever been in.” Never mind that it features only two bedrooms, few closets and a mere 1,121 square feet. The sweeping ceiling and daring focal point–a freestanding inverted cone fire pit under a floating-disk hood in the living room (“the human sacrifice area,” Roden jokes)–completely captured the Rodens’ imagination. They snagged it for less than $300,000 last spring.

After handing Roden a rare black-and-white original image Of the house, Doe can’t help dispensing some of his usual unsolicited advice. “You gotta get rid of those two big plants, keep everything low so you can see the curve going around,” he tells Roden, critiquing the exterior. The next minute, he approve the concrete coving on the living room floor.

With more and more clients like the Rodens and the Marshalls seeking architectural homes, Doe worries about the dwindling supply. His solution? To discover hidden gems in underappreciated neighborhoods, like the Trousdale area of Beverly Hills, and to find interesting new properties by current architects such as Kendrick Bangs Kellogg, Steven Ehrlich, Eric Lloyd Wright and the young design team of Koning Eizenberg Architecture.

In the meantime, the realtor is excited to have closed escrow on another major piece of architecture that he helped save from ruin. A modernist masterpiece by Hamilton Harris, it was built in 1950 on a Beverly Hills promontory off Coldwater Canyon. On a clear day, it offers a view of the Long Beach skyline. It’s not Doe’s listing, but the buyer, a young entertainment executive, is his client. The seller, film producer Larry Gordon, bought the house five years ago, started to renovate, then changed his mind. With its low projecting roofs and cantilevered sections, the two-story house was once as striking as cubist art; now some think it’s a multimillion-dollar eyesore. “The last three successive owners made a mess of the house–added new picture windows, didn’t understand the aesthetic,” Doe says. Today it’s his favorite L.A. property. “It’s one of the four or five most important houses I’ve sold in 25 years,” he says. And in a way, it’s taken him full circle.

He first saw the 8,000-square-foot house in 1974 when it was on the market in its original condition for $275,000 (the selling price 24 years later: in the neighborhood of $3 million). “I begged George Hamilton to buy it then, but he said he was putting his money into pork bellies,” Doe laments. Now L.A.’s enduring architectural advocate has his work cut out for him–urging a new buyer to do the right thing. “The entire basic shell is all there,” he says. But as he surveys the tacky mirrored walls in an otherwise lofty living room and the mournfully suburban Brady Bunch kitchen redo, you can practically hear his mind churning.