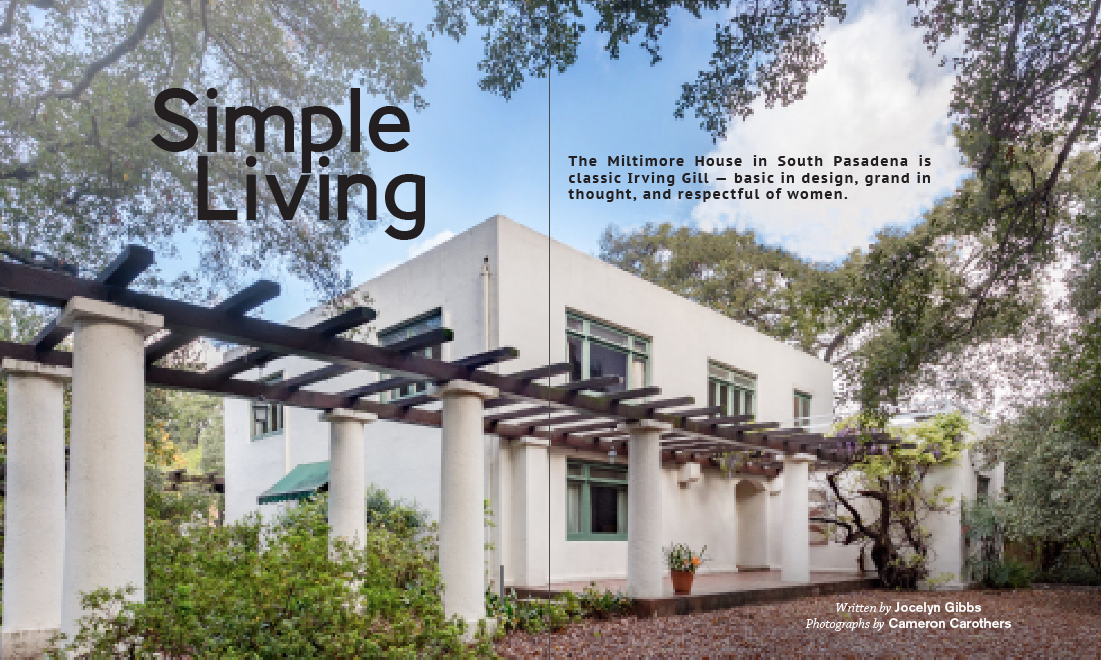

The Miltimore House in South Pasadena is classic Irving Gill — basic in design, grand in thought. No wonder it is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Written by Jocelyn Gibbs

Photography by Marvin Rand and Cameron Carothers

Architectural historian Esther McCoy once called Irving John Gill one of America’s “few wholly original architects.” Though he was nearly forgotten in the decades after his death in 1936, McCoy brought him new attention in her still-important 1960 book, Five California Architects (landing him in the esteemed company of Charles and Henry Greene, Rudolph Schindler and Bernard Maybeck). In her Gill essay, she made the case for his originality and portrayed him as a builder whose plain forms grew out of his honest expression of structure. More recently, historian Thomas S. Hines further expanded our understanding of Gill’s stature by contextualizing his work within the Arts and Crafts movement, the Progressive era, and the rise of early modernism in his 2010 treatise, Irving Gill and the Architecture of Reform.

The Miltimore House in South Pasadena is one of the purest expressions of Gill’s intentions. Not as grand as his famous Walter Dodge House in West Hollywood (sadly, a casualty of the wrecking ball in 1970), the Miltimore house is one of the few intact examples of his fervent architectural beliefs. The simple cubic form is tied to its landscape through garden structures and terraces. The interior embodies the progressive ideas of early twentieth-century reform movements regarding efficiency, health, and “women’s work” that were integral to Gill’s residential designs (this impulse may be what drew so many strong and independent female clients to his talents).

In this case, Mrs. Paul Miltimore was the client listed on Gill’s original drawings for the house. Genealogical records show that she was born Polly Basset Vail in 1857, but, at some point, she began to use Paul as her given name. Curiously, family lore suggests that she changed her name because so many people mispronounced Polly. In 1898, Polly “Paul“ Vail married Daniel O’Connor Miltimore (1840-1901) in Decatur, Illinois, where the L.A.-based businessman had interests. Paul had been the Macon County Court stenographer (where her brother was a judge) and was active in social organizations. Meanwhile, Daniel Miltimore was a widower whose first wife, Lucy Louise Becker, had died in 1896, leaving him with two grown daughters, Minnie Catherine and Grace. A son, H. E. had died in 1887.

Miltimore first appears in the Los Angeles City Directory in 1884-85 with the occupation of farmer. The 1887-88 directory lists him as a “capitalist” and director of the University Bank of Los Angeles. Minnie Catherine was one of three students—and the only female—in the University of Southern California’s first graduating class in 1884, becoming the school’s first valedictorian (before earning a Master’s degree and becoming an assistant faculty member). Her sister also attended USC and their father was on the university’s board of directors.

Of equal note, Miltimore was the founding president of the Los Angeles Olive Growers Association, formed by a group of midwest businessmen in 1893. The association purchased 2,000 acres in the San Bernardino foothills from the Maclay Ranch in what is now Sylmar. According to the Los Angeles Times, the association planted 200,000 olive trees beginning in 1894, which was to become the largest olive grove in the world by 1906.

In 1901, shortly after his marriage to Paul, Miltimore died of “apoplexy” (probably a stroke) in British Columbia, where he had likely gone to convalesce. As is customary for a widow, Paul was thereafter addressed by her given name, i.e., Mrs. Paul Miltimore, not Mrs. Daniel Miltimore, which further explains her name on Gill’s drawings. Not much is known about Paul after his death. But a Miltimore family member reports that she and her stepdaughters were remembered as “accomplished and literary.” She also served briefly as vice-president of the Olive Growers Association and Minnie Catherine, three years her junior, was secretary of the association. They remained close friends and continued to live in the same household after Miltimore’s death.

It was in 1910 that Mrs. Paul Miltimore purchased a lot in South Pasadena and commissioned Irving Gill to design the house where she and Minnie Catherine lived for the rest of their lives. How Paul chose Gill is a mystery. Some historians believe that Homer Laughlin, Jr. was the link since the architect designed a home for the prominent L.A. businessman in 1907-08 on 28th Street near USC—probably Gill’s first solo effort in the city (he and his San Diego partner, William Hubbard, designed an L.A. house for O. J. Barker in 1902).

Perhaps Miltimore’s role as a banker and businessman put him in touch with the Laughlin family. Homer Laughlin Sr., a few years younger than Miltimore, came to Los Angeles in 1897. The office for the Los Angeles Association of Olive Growers was across the street from the Laughlin Building in downtown Los Angeles. Or perhaps Paul knew Ada Edwards Laughlin, the younger Laughlin’s wife, through social or cultural activities.

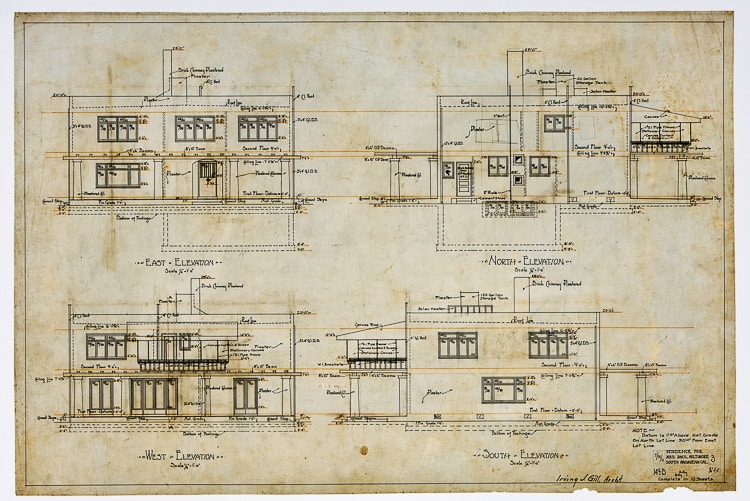

A 1910 survey map of Mrs. Paul Miltimore’s lot shows that the east end of the lot along Chelton Way was planted with nearly 30 oak trees of varying sizes. Gill carefully positioned the house to preserve the trees. The adjacent lot to the south had a house on it but the lot to the north was empty, which explains the apparent expansiveness of the grounds in early photographs of the Miltimore House. The dimensions of the front and rear elevations each form a double square. The width and height of the side elevations come close in relationship to the golden rectangle (1:1.618). These careful proportions are characteristic of Gill and carry through to his interiors, even in his smallest cottages.

Also characteristic of Gill is his use of “green rooms,” which extend living spaces into the landscape. The two large terraces that extend across the front and rear elevations serve as outdoor living rooms for the Miltimore house. The terrace floors are paved with 12-inch square tile and roofed with trellis supported by simple plastered concrete columns.

The columns at the front and back extend beyond the terraces by three bays to span the driveway, a detail that does not appear on the original plans. The columns on the terraces are without bases; those on the ground sit on plain square bases. Even before wisteria vines covered the trellis, these pergolas were the most prominent feature of the house. They were designed to be covered with vines and to decorate what Esther McCoy called the “chaste simplicity” of the plain, white rectangular mass of the house. In this way, the Miltimore house is a reminder of how powerful Gill’s modesty can be, especially when framed by the lushness of nature.

Throughout his career, Gill used a simplified Tuscan column in his garden rooms, terraces, and interior courts. His prominent use of columns is in keeping with his belief that the architect should go back to “the source of all architectural strength—the straight line, the arch, the cube and the circle—and drink from these fountains of Art that gave life to the great men of old.” He railed against the “architectural crimes” committed by imitating historical architecture, such as the California missions and Greek temples. But, following Sullivan’s teaching, he referenced the past in order to create a “new American architecture” from platonic versions of classic architectural elements. Gill even included a subtle pilaster where the end of the pergola meets the wall.

With the exception of the luxuriously spacious living room and master bedroom, the interior of the Miltimore house is conventional in its layout. The central hall plan, typical of Gill’s houses, divides the first floor in two, with the entrance hall connecting the front terrace to the back terrace through the alignment of the front and back doors. The large living room is on the south end and extends the full width of the house. A large dining room overlooks the rear terrace. On the original plans, a pantry, kitchen, and screened utility porch fill the north end of the house. Access to the basement is off the screened porch. A utility porch on the original plans is actually a one-room, single-story extension; a maid’s room with bath, not on the original plans, was apparently built at the same time as the rest of the house (it appears in the earliest photographs).

Mirroring this extension is another one-room extension on the west side of the house, off the dining room. This is a small light-filled room which the current owners call the painting studio. Esther McCoy believed that this room was built in 1911. The kitchen was remodeled in 1958; the windows inserted above the sink are in the same style as other windows in the house, but made of steel instead of wood. A comparison of the original plans and elevations with the HABS drawings, drawn in 1988 for the application to the National Register of Historic Places, makes the changes clear.

Gill inserted a skylight above the main stairway, details for which appear on the original drawings. On the second floor are four bedrooms and two baths. Directly above the living room, and mirroring it in size, is the master bedroom. It also includes a fireplace. Paul Miltimore clearly envisioned this room as her private living quarters.

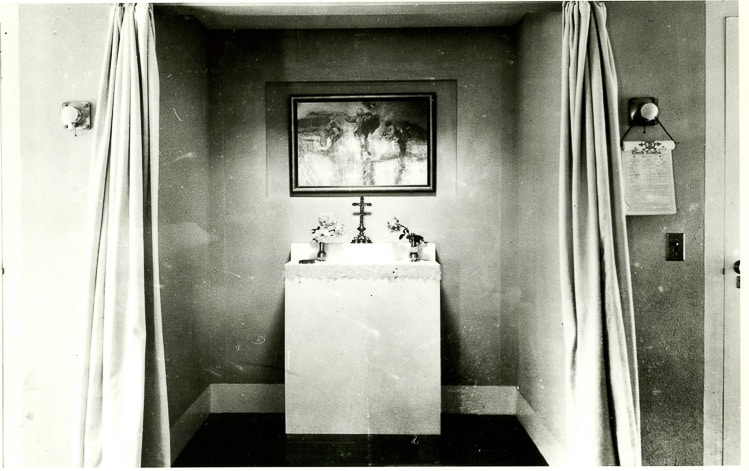

In the west end of the master is an alcove that is identified on the plans as an “oratory.” An early photograph shows a small altar in this space, supporting a cross and flower vases, with a painting of a religious subject hung on the wall above. The ceiling of the oratory has a small skylight, which shows on the original plans only as a faint pencil sketch. Commodious closets flank the oratory. The closets and oratory seem to have been built as one unit across the west end of the master bedroom, with a shared floor that is raised four inches above the floor of the room. The floors of all closets in the house and both upstairs bathrooms also have raised floors. This was one of Gill’s many innovations to make cleaning easier and to keep out dust. The effect of the raised floors is that the main volumes are clearly delineated from ancillary ones, giving a crisp appearance to the rooms.

The master bedroom has its own bathroom. Outside the master bath and the adjacent bedroom (chamber no. 4 on the plan) is a sleeping balcony, which originally had galvanized pipes to support canvas curtains and an awning. Both bathrooms include a wainscoting of magnasite, a composite material more commonly used in the 1920s for “woodstone” floors and stairs. Gill often used magnasite in kitchens and baths to create a hard, mold-free, easy to clean surface. Three of the bedrooms include electric bells for calling down to the help in the kitchen.

Gill detailed all the moldings and doors in order to further simplify the house and eliminate surfaces where dust could accumulate. The wooden doors are single panels of Oregon pine. The moldings at the floor and ceiling, and around doors, windows and cupboards, are flush with the plaster walls. All this trim was painted Oregon pine that varied in size, depending on location. Gill designed the built-in cupboards for the dining room, kitchen, and the bathrooms, as well as the bookcases in the living room.

Very early in his career, the architect experimented with wall construction methods in order to eliminate the interior cavities that could act as flues in a fire. The Miltimore interior walls are relatively thin, made up of one-inch board built up with lathe and plaster to no more than four inches in depth. His plans show a solar-heating system on the roof with a 120-gallon storage tank. It is not known if this was ever installed.

During the time Paul Miltimore lived in the house with her stepdaughter, she apparently made no changes to the property. Minnie Catherine died in 1935 and Paul died three years later. The house seems to have satisfied new occupants over time, since it has remained intact with only minor changes. John Shaw purchased the property from the Miltimore estate in 1940. Benjamin and Virginia Holt moved into the house in 1952 and the Holt family continued to live there till recently.

Over the years, Gill’s own career was bracketed by the nation-wide economic depression of 1893—the year he left the Chicago office of Adler and Sullivan and moved to San Diego—and the Great Depression of 1929. The Panic of 1893 coincided with the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, for which Louis Sullivan designed the transportation building, the only major structure at the Expo that was not in the conservative neoclassical style. Gill worked on this project, and perhaps other commissions in the Adler and Sullivan office between 1891 and 1893, under the supervision of Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1893, Wright left Adler and Sullivan to open his office in Oak Park, Ill. and Gill moved to San Diego to begin his own architectural career. He was 23 years old.

In San Diego, it took Gill several years to apply all the concepts he had learned in Chicago while working for Sullivan, widely considered the father of modern architecture. His call for a new architecture that turned away from historical precedents and relied upon honesty and individualism was the inspiration that drove Gill’s most advanced designs. As he wrote in his 1872 essay, “Ornament in Architecture”: “I take it as self-evident that a building, quite devoid of ornament, may convey a noble and dignified sentiment by virtue of mass and proportion.”

Between 1907 and 1916, Gill produced buildings rooted in Arts and Crafts ideas about the honest use of materials, yet they also foretell later avant-garde designs that were to appear in Europe and the U.S. His simple, undecorated forms have none of the interior complexity that is found in the works of Richard Neutra and R. M. Schindler. Yet, when those two Austrian emigres first encountered Gill’s architectural abstractions in Los Angeles, they saw a kindred avant-garde spirit. In fact, after he moved to Los Angeles from Chicago, Schindler photographed an early Gill building in San Diego. On the back of the photograph he noted that it was reminiscent of Louis Sullivan. At the same time, Neutra heralded several Gill buildings—Horatio West Court, the Mary Banning House—including photographs of them in his 1930 book, Amerika.

It added to Gill’s early success in San Diego that many of his clients were the business and cultural leaders of that time. His career grew as the city did: He built the substantial Timkin house; the Bishop School in La Jolla; and he enjoyed a short-lived assignment as chief architect for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition. By the time Gill’s nephew, Louis Gill, joined the firm in 1911, the office employed six draftsmen, a supervisor and a secretary.

We have a less cohesive picture of Gill’s Los Angeles period because many of his drawings from those years were lost. Yet, the histories of his clients there reveal intimate slices of the city’s cultural and economic life and fill in details of Gill’s career as he traveled back and forth from San Diego. The Miltimores, for example, not only had ties to the agricultural economy of Southern California and one of the city’s major educational institutions, but the family was part of the large migration of midwesterners who flocked to California, lured by the promise of the Golden State. They were to become Gill’s clients at the height of his career, along with the Laughlins and L.A. society photographer George Steckel. Although the latter’s house was never built, Gill’s archive at UC Santa Barbara includes a full set of drawings for the project. So, eventually, in 1912, the architect opened an L.A. office in preparation for his extensive work for the new South Bay city of Torrance.

Overall, Gill’s domestic interiors demonstrate his intense focus on efficiency and his concern for reducing the toil of house cleaning, while enhancing the health of a home’s occupants. Once he had developed his characteristic style of simplified forms, he decorated the surfaces only with light and shadow, subtle color, and plant material. He refused or quit jobs when he was asked to change his ideas. But when he found the right clients—especially progressive, self-reliant women—the results were highly successful for everyone. He could have been describing the Miltimore House when he wrote in 1916, “In California we have long been experimenting with the idea of producing a perfectly sanitary, labor-saving house, one where the maximum of comfort may be had with the minimum of drudgery.”

Decades later, when the architectural photographer Marvin Rand photographed the Miltimore House during the sixties, it looked as advanced and optimistic as it does today. As Gill wrote in his 1916 manifesto: “If we, the architects of the West, wish to do great and lasting work we must dare to be simple, must have the courage to fling aside every device that distracts the eye from structural beauty, must break through convention and get down to fundamental truths.”

Contact us about this property:

Error: Contact form not found.