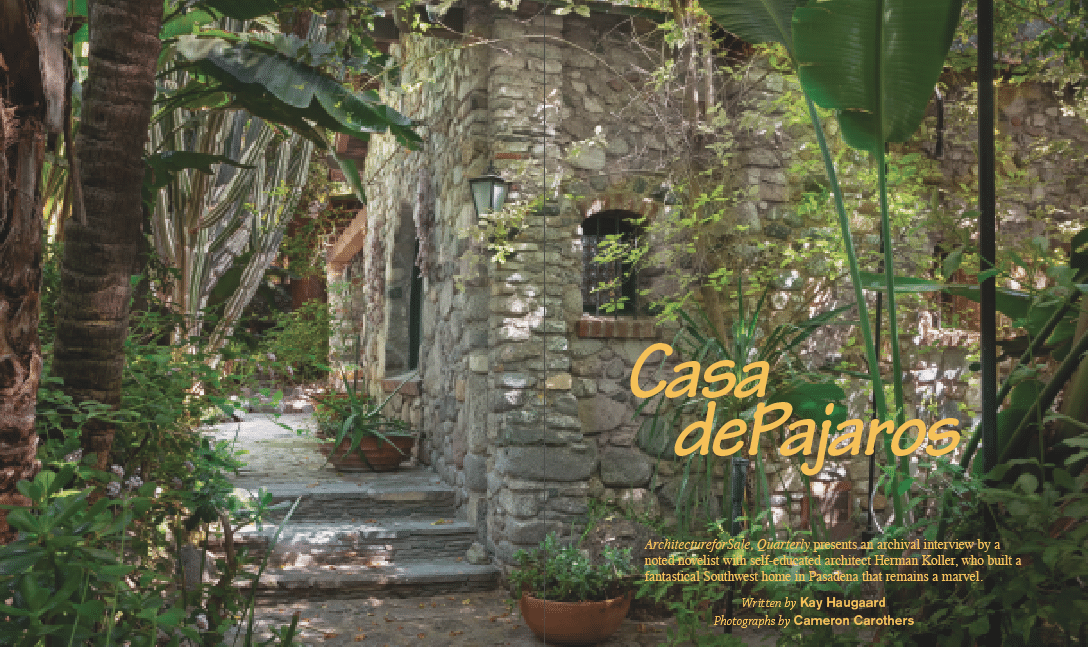

ArchitectureforSale, Quarterly presents an archival interview by a noted novelist with self-educated architect Herman Koller, who built a fantastical Southwest home in Pasadena that remains a marvel.

by Kay Haugaard

Herman Koller is a slight man who looks at you like an old prospector squinting into the sun. But don’t let his unassuming style fool you. He has accomplished an enormous feat. It required a combination of back-breaking labor, the zeal of a dedicated collector and the discerning eye of a sensitive artist to build “Casa de Pajaros,” his unique stone and brick home, a museum-quality example of old Southwest architecture.

When Koller, a Southern California transplant of Pennsylvania Dutch stock, began building his house in the foothills near Pasadena, the style surprised his relatives visiting from Pittsburgh. “Why didn’t you build a German-style house with a steep roof?” they wanted to know.

But he would have none of this. In his travels through the Southwest he had absorbed the flavor of the country and its regional designs and he knew just the kind of house he wanted.

Koller had been a wandering, outdoors kind of man, close to nature, a man who had the enviable courage to follow his inclinations wherever they might lead him. They have led him through such widely disparate activities as attending Pittsburgh art schools to exploring the Florida Everglades. There, he became known as “Alligator Joe” because he captured baby alligators and shipped them all over the United States.

Later his restless curiosity led him to Central America, where he went to seek gold but found a revolution instead. So his hunt ended anti-climactically in Spanish Honduras. By the time he had returned as far as California, Koller was too broke to continue the trip back to Pennsylvania, so he stayed here. He discovered he had an affinity for this southland of strong sun and color.

He especially loved the desert, its harsh and beautiful vegetation, its formations of infinite subtle shapes and colors. The artist in him wanted to soak it all up, digest it, and from it produce something beautiful of his own. His ambitious choice was to create a traditional Southwestern-style stone house that would strongly acknowledge the area’s Spanish heritage.

A remarkable singleness of purpose enabled him to keep his enthusiasm and direction during the 17 years (1928 to 1945) that it took him to produce the house. He worked only in his spare time, after finishing his regular labors as a house painter. This was no “do it yourself” project that got away. In his wanderings that led him as far south as Central America and north to the Monterey Peninsula, through Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, and California, he accumulated sheaves of sketches, paintings and photographs of buildings. In Mexico, he found particular inspiration in the old buildings of Matamoros. When he wasn’t wandering he was reading about Southwest art or visiting museums. The outstanding Southwest Museum in Highland Park became one of his favorites.

Later he made a precise scale model. He laughs as he tells how some of his neighbors were concerned by what appeared to be a huge junk heap in his front yard when the house was only half finished. “But even then,” he shakes his finger for emphasis, “I knew where every piece of that stuff was going.”

Once begun, the house became a way of life; a passion he pursued widely in his search for the right kind of materials. He never owned a truck so four cars were eventually completely “used up,” as he says, carrying heavy stones from his far-flung forays from Tucson to Tahoe. He brought grey sandstone from old breakwaters near Santa Barbara. He hauled home the distinctive stones of Palos Verdes and Bouquet Canyon, and a peculiar type from Pacoima that looked like wormy driftwood. It was used to handsome effect around his goldfish pond.

“I’m a scavenger from way back,” he says, describing his adventures in accumulating building materials. “When I was a kid I used to search through the city dump every Sunday. There aren’t many good ones left, but I found a good one up near Truckee where I found lots of stuff as far back as the 1800s.”

This habit of rummaging for materials from dumps and demolished buildings has made his home a sort of structural history book of much of the San Gabriel Valley. Some of the mementos he has built into the house are: Large beams from an old flour mill that burned down, near Raymond Avenue in Pasadena; big, red stones from the old Los Angeles City Hall and bricks from the extinct Hotel Raymond of Pasadena. The belfry tower was built entirely from bricks from the Santa Barbara Mission after a big earthquake decades ago did so much damage.

“I asked the priest if I could have some, and he said to take all I wanted. So in two trips I had enough for my belfry.”

Each of the bricks around the arches in the patio arcade are adobe and equal in size to five ordinary bricks. Many were handmade in a Pasadena adobe factory which is now long gone. The patio, an interior, arcaded court of dull red brick, is a marvel of workmanship.

“I always was one to watch workmen doing things,” he states simply. “Whenever I saw a stone mason or bricklayer working, I would pester him with questions. I saw arches built a few times and when I wanted to do it myself I got a book and studied it and built a scaffold and did it.” With this philosophy he was able to complete the entire house except for the wiring and roofing.

The massively handsome garden wall, which is 18 to 20 inches thick, is a rich conglomeration of flagstone, an occasional stone angel wing from a broken monument, scrap heap tile and carloads of rock from miniature golf courses. When the rage for this game collapsed in the 1930s, the courses became a rich source of building material.

The lofty driveway structure is made of old railroad ties. In true early West style, it is not nailed, but held together by heavy metal straps and bolts. Hanging from it is an oxen yoke that traveled west from Connecticut, but by freight train, not wagon train.

All these things Koller has put into the melting pot of his imagination to produce a thoroughly integrated work of art in which every element contributes to the total effect. He points out the beautifully authentic details: The green, round topped gate that echoes the stone arch of the wall, the vertical sundial on the south wall, the curious masonry chimney pot detailing. “Not many people see these things,” he says proudly. “You have to have an educated eye.”

His project did not end with the building of the house. He has lavished the same care in selecting what you might call the accessories. An old ox cart rests in the front yard. Sun lavendered bottle necks, strung into “necklaces” hang against a stone wall. In the belfry hangs a heavy iron bell, gift of a Midwest farm but completely naturalized by its setting. In the patio rests a string of peppers near insets of hand-painted Spanish tile and wrought iron lanterns from old Spain. There are stones and relics of his desert wanderings; a donkey pack saddle, a woven Paiute water jug, a big Mexican olla. Every detail belongs, from the rusted teakettle filled with bullet holes to the longhorn skull resting by the yucca.

The plants, too, have been selected to harmonize with the desert quality. A “Pipe Organ Cactus” and a crested night-blooming cereus are two monumental examples. But every corner reveals such strange, spiky, undulating, wildly beautiful plants as the climbing aloe over the front gate or the “crown of thorns,” a climbing cactus, now red with blood-like blossoms. Here is a collection of sedums, agaves, euphorbias, cacti, which would rarely be seen in a private garden.

Now in his 70s, Koller lives alone in “Casa de Pajaros,” which he describes as “my little paradise.” He has embarked on a new project in landscaping his hillside. He has cut a trail up the near-vertical bank and has planted it with spiky blue century plants, yucca, geranium and nasturtium, which were blooming in blinding profusion when I visited him last. He carefully picked nasturtium seed pods and pressed them into my hand before he took me up the steep trail. He trotted before me, agile as a ground squirrel, pointing out the branch bridges and timber steps he was working on. When we reached a big oak tree I sat down on a bench, huffing and puffing. Yet, Koller was climbing to greater heights to view the whole of his little paradise and, not content to just stand and admire his remarkable accomplishment, he was already speaking of his plans for additions and improvements.

Now in his 70s, Koller lives alone in “Casa de Pajaros,” which he describes as “my little paradise.” He has embarked on a new project in landscaping his hillside. He has cut a trail up the near-vertical bank and has planted it with spiky blue century plants, yucca, geranium and nasturtium, which were blooming in blinding profusion when I visited him last. He carefully picked nasturtium seed pods and pressed them into my hand before he took me up the steep trail. He trotted before me, agile as a ground squirrel, pointing out the branch bridges and timber steps he was working on. When we reached a big oak tree I sat down on a bench, huffing and puffing. Yet, Koller was climbing to greater heights to view the whole of his little paradise and, not content to just stand and admire his remarkable accomplishment, he was already speaking of his plans for additions and improvements.

Contact us about this property:

Error: Contact form not found.