“I found a building site. . .10 minutes from Hollywood. . .a thousand feet above sea level, that is to say above Hollywood and it is still a part of Hollywood. . .on the peak of a mountain with a view to the south where Los Angeles and Hollywood lie like an ocean; a view to the east where one can see the snow-covered Sierras; a view to the west where one can see the ocean and the fairytale island of Catalina.”

— Letter from Galka Scheyer to her beloved artists, the “Blue Four,” 8-2-1933

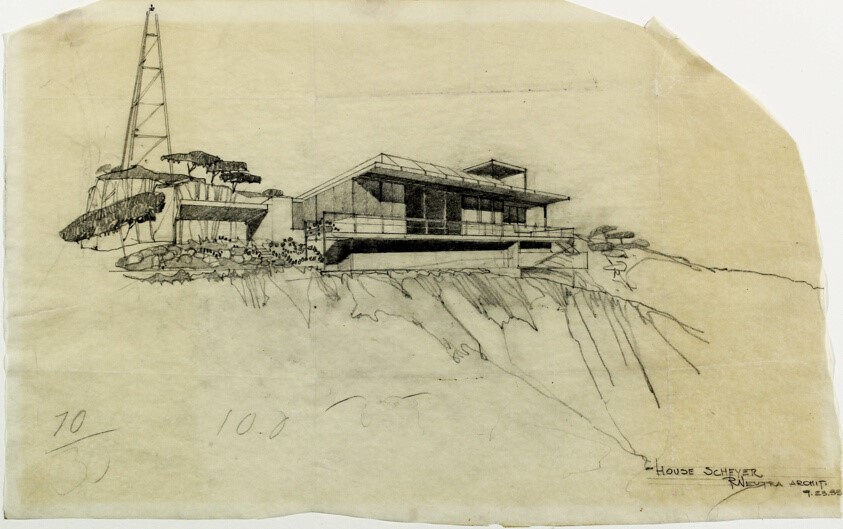

When Galka Scheyer selected Richard Neutra to design her first real permanent home in the United States in 1934, this was a triumph for the Vienna-born architect. Scheyer had previously lived in one half of Schindler’s Kings Road House (as the Neutras had themselves when they first came to Los Angeles in 1925). She knew most of the European-born Modern architects in Los Angeles (or is that…all of them)?

She had been leaning originally towards hiring the suave designer (and postwar Case Study not-quite ‘architect’) J.R. Davidson. Davidson, Berlin-born, was already celebrated as the designer of the very famous Cocoanut Grove nightclub. And, from the late 1930s, for the revamped Sardi’s and a small number of Modern houses, particularly the residences for Herbert Strothert (1938) and Nobel-Prize-winning author Thomas Mann (1942) . (Ironically, Davidson was hired to recreate the West Coast outpost of the theater & film world landmark on Hollywood Boulevard only after a fire had destroyed Rudolf Schindler’s earlier version of the restaurant).

Scheyer knew designers Kem Weber and Paul Laszlo; and she had been a champion of Rudolf Schindler… until she spent a year as his tenant at Kings Road in 1931. Typical landlord-tenant frictions had then gravely damaged their friendship, unfortunately.

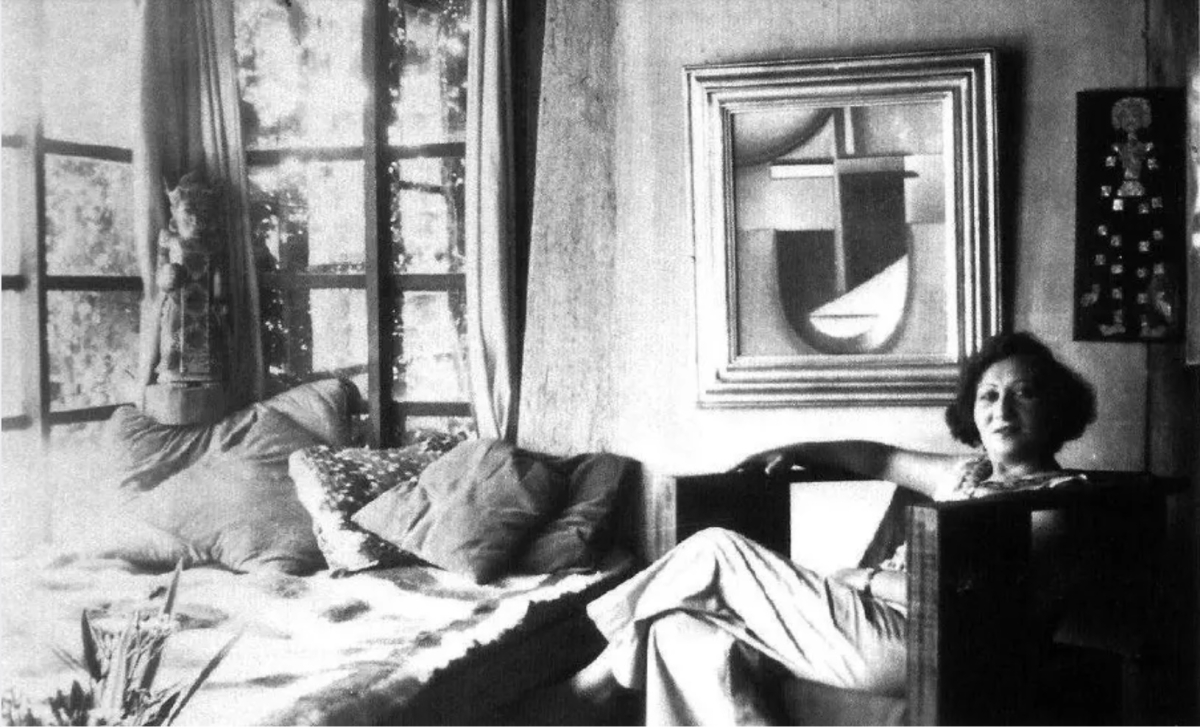

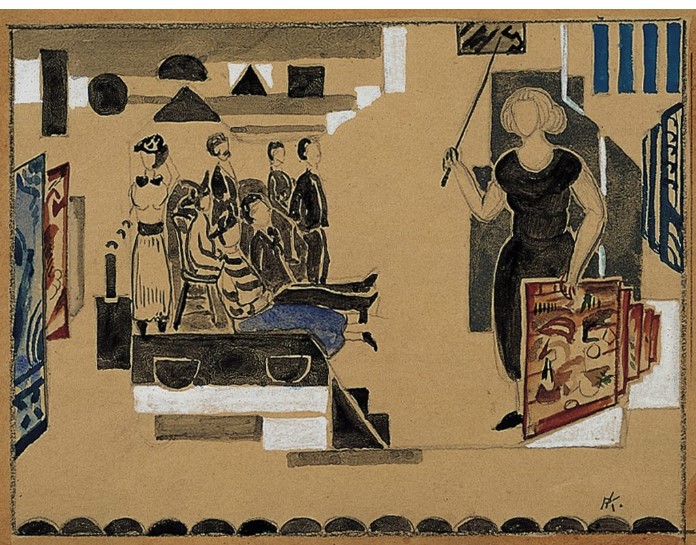

Before this unfortunate episode, Scheyer had called Schindler “her 5th Blue King” (as documented by scholars John Crosse and José Parra-Martinez) and passionately advocated for other art world figures to hire her friend. Just as she had promoted her beloved “Blue Four” painters (Wassily Kandinsky; Paul Klee; Lyonel Feininger and Andrej Jawlensky) from the day she arrived in the United States in 1924.

Architecture specialist Crosby Doe Associates is especially proud of selling the Galka Scheyer house this year in a far from easy market environment. The structure was just the sixth ground-up residence Neutra designed in the United States: Beginning with his landmark Lovell Health House of 1927 – 1929 (itself sold by Crosby Doe Associates last year); and after his own VDL Research House on Silverlake Boulevard.

The listing agents, Crosby Doe and Ilana Gafni, are also gratified that the new owner intends to honor in some part the house’s original purpose as a showplace for the modern visual arts. This really is the principal reason for the house’s existence. This was not just a strong, single woman’s refuge: Scheyer conceived of it as a showplace and salon that would foster continuing progress in the visual arts and architecture all at once. (Though it also fulfilled her desire for a perfectly private hilltop where she could “sunbathe nude.”)

Also remarkable is that art impresario/‘missionary’ Galka Scheyer was the first to build on her street near one of the topmost crests of the Hollywood Hills. A pioneer even there, she named the street herself! Blue Heights Drive commemorates this formidable woman. An art-eyrie nearly touching the sky, the house she commissioned from Richard Neutra in 1934 is a classic expression of Neutra’s version of International Style modernism. Its wild and remote atmosphere was all the stronger originally as it was reached by a rugged dirt road. Even today, adventuresome: Parts of the paved street skirt steep cliff-edges.

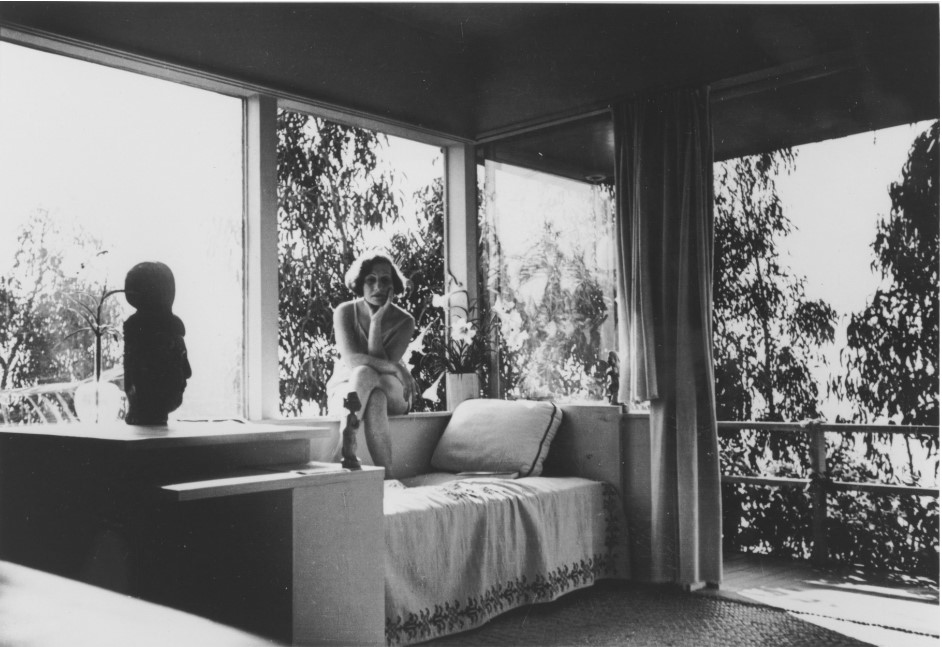

But it is not like all such houses, even Neutra’s other houses of the period. One approaches it side-on, with little sense of what is actually there. Then, going under a classic ‘spider-leg’ beam, one walks under the full length of the house, then up an exterior staircase and through the door. Turn left, and one enters the high-ceilinged living room almost at once. With its panoramic views, this one large room dominates the design and takes up the majority of Neutra’s interior square footage. Indeed, on occasions Scheyer had a bed in this grand “studio” and slept here rather than in the smaller bedroom, per scholars John Crosse and José Parra-Martínez.

In sharp contrast, that original bedroom tucked behind the modestly sized kitchen (and even the small second floor bedroom added by architect Gregory Ain) are sufficient for sleeping and little more. An economical “fireproof” (so far, thankfully) office/painting-storage room and the dining room are just enough space for their functions. The long terrace along the south wall of the house facing the view is much more spacious and inviting. Scheyer, one thinks, was not one to linger in bed as dawn came — and dawn’s light comes early, way up this high, on her Blue Heights.

Understandably, the visitor turns back quickly to the living room. A dramatic space for showing the paintings that Scheyer attempted, undaunted by frequent rejection, to sell to Hollywood luminaries, this large, sunny, glorious room with south and west moving ‘walls’ almost entirely of glass functioned as a salon. (Neutra did not, however, provide much help in the display the paintings themselves. Scheyer had to plant trees to reduce the bleaching effect of the nearly direct southern exposure).

This main space could be enlarged when a 16-foot long (4.9 meter) steel-framed sliding door was opened to the terrace for entertainments and events. Which Scheyer excelled at organizing: Up to Blue Heights came European émigré artists, architects, directors and actors; 30’s movie stars (Marlene Dietrich; Garbo!) American avant-garde budding composers (John Cage); photographers; art students and collectors. A ‘Who’s Who’ assortment came to Scheyer’s party-cum-lecture events here, along with art aficionados not famous.

In fact, longtime ArtForum editor & native Angeleno Amy Baker Sandback has dubbed this house a “home-gallery-church of advanced art.” (Via a very personal 1990 ArtForum tribute to Scheyer’s influence. And that of Scheyer’s all but priceless collection of paintings that are now held by the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.) Few of Neutra’s houses so strongly bear the imprint of their commissioning original owners. Still.

“Twenty lectures in my house . . . hanging pictures, so splendidly, so lovingly, each related to the others [paintings] with glorious names, Rousseau, Van Gogh, Cezanne, from the dead, and modern French artists . . . in combination with all the treasures that my Blue Kings have lent me. Hanging takes an entire day. Cleaning, filling the house with flowers, a second day. The lecture, a third, and cleaning up afterward, a fourth.”

[Letter from Galka Scheyer to the Blue Four, March 10, 1936. Quoted in “The Art Lover: Galka Scheyer’s Higher Calling” by Darcy Tell. Published in the online magazine East of Borneo, December 2, 2010]

Indeed, Galka Scheyer’s house, (like Schindler’s Kings Road House and Wright’s Hollyhock House) is a key landmark of the cultural history of Los Angeles — really, of the United States as a whole. Through her teaching, her lectures and her advocacy, Scheyer had a direct and measurable influence on young American artists in many different media. Art in California would not have been what it became without her contribution.

Not just artist Peter Krasnow (work pictured above and below), but local gallerist Earl Stendahl later expressed profound gratitude for Scheyer’s teaching and influence. Her role in some of the key architectural commissions of the interwar was in fact crucial, a story only coming to light via recent research on this facet of her time in Los Angeles.

Subsequent Posts will examine the connections between the architect-mentors, artists and patrons of the interwar period in Southern California and this confident postwar arrival of the newest of the New, now made in America. The degree to which key individuals in this group knew each other remains astonishing. Galka Scheyer was at the very heart of this network, despite her many travels elsewhere pre-1934. She had quickly established herself among the most well-connected and persuasive figures among them – although far from universally liked or respected by some of them, as shall be shown.