Galka Scheyer was an extremely important figure for American art and architecture. Very much like painter (and Marcel Duchamp-collaborator) Katherine S. Dreier (1877-1952), the critical early apostle for European Modernist art back East in New York City after 1913. And Scheyer’s East Coast doppelgänger, an Alsatian Baroness, the painter Hilla von Rebay (1890 – 1967) who benefited from a longer life and a great, rich American patron in Solomon Guggenheim. Rebay was to do in New York what Scheyer had hoped to upon her arrival there in 1923, becoming Kandinsky’s greatest New World champion during the 1930s and ’40s

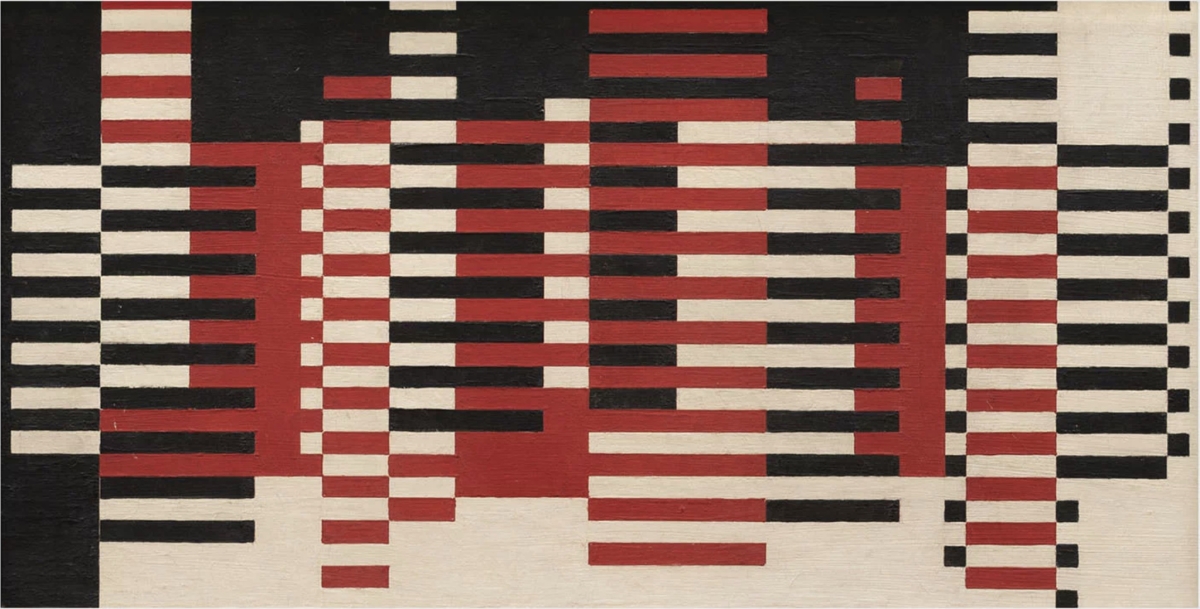

These earliest advocates helped plant the seeds for future American art movements that flowered right after World War II – along with emigrant/refugee teachers like Joseph & Anni Albers (on the faculty at Black Mountain College from 1933); Laszlo-Moholy Nagy (in Chicago from 1937); and Herbert Bayer, from 1938 onwards. All of these last four were from the Bauhaus itself, directly.

Conventional histories of the origin of the first indigenous American abstract painting tradition to last all emphasize the (undoubtedly great) contribution of the painter and teacher Hans Hofmann (1880 – 1966), who emigrated from Germany to the USA in 1932. Though he had taught in California in two separate earlier sojourns (at Berkeley and then again and at the Chouinard Institute in Los Angeles), Hofmann based himself largely in New York and Provincetown after his permanent emigration. He taught continuously in the USA from 1932 until he retired from teaching in 1955.

Teacher to younger artists like Lee Krasner – and the great Californian designer Ray Eames, before her marriage! – Hofmann was a key influence on the younger Modernist painters who created the group “American Abstract Artists” in New York City in 1937 (on which, more in the next post).

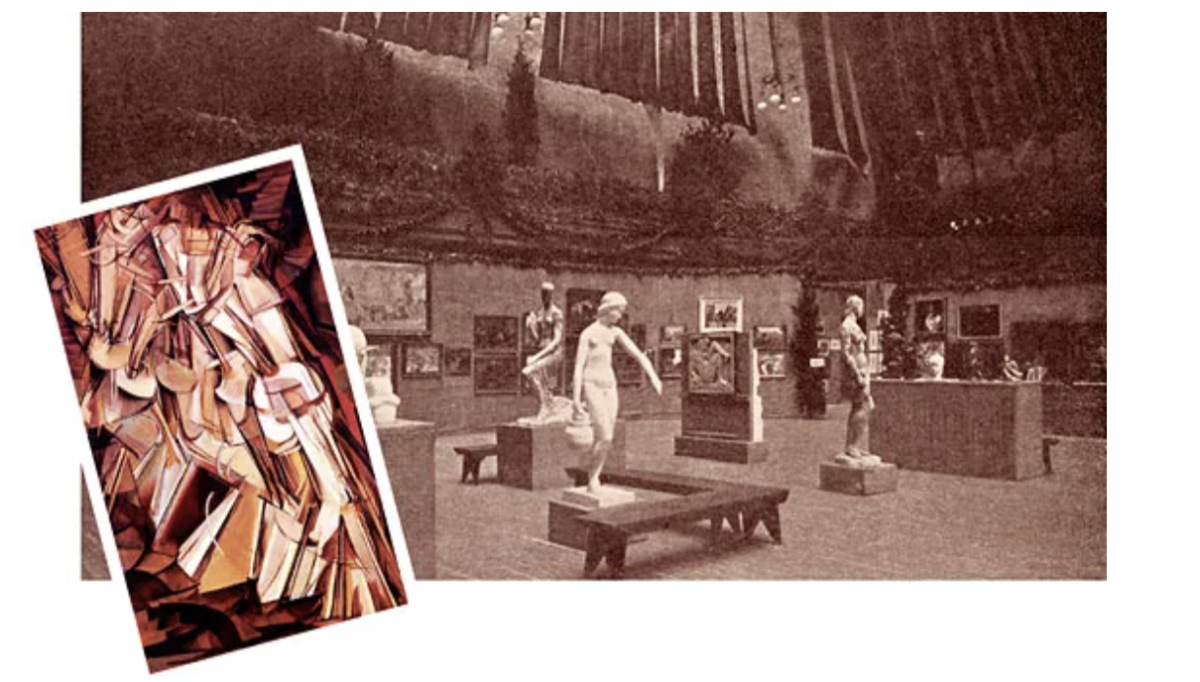

While acknowledging Hofmann’s direct role in art as a teacher, we should remember that nearly two decades had passed since the earliest exposure of European Modernism to Americans at the 1913 Armory Show. A small handful of Americans and recent immigrants kept exposing anyone who would come look to the latest innovations in art from Europe, after a flurry of experiments up to roughly 1916. But hardly to acclaim or widespread approval.

The almost universal reaction of every citizen of an otherwise future-oriented democratic republic to the paintings that were harbinger of a Machine-Age culture was … mockery. Incomprehension. Rejection. Only a very small handful of artists, critics and collectors swam against an American current that – despite an initial sensation after 1913 in New York that was all-too brief – rejected any image that was difficult to relate to a recognizable object.

While a small but not insignificant group opened their minds to some Cubists (Picasso above all) and their French and other predecessors labeled “the Post-Impressionists”: Van Gogh, Cézanne, and others…in general, the alien art virus excited American antibodies that overwhelmed the initial sensation:

“It makes me fear for the world,” one dismayed art connoisseur told [the Chicago Tribune’s art critic regarding the Armory Show] “Something must be wrong with an age which can put those things in a gallery and call them art. The minds that produced them are fit subjects for alienists and the canvases—I can’t call them pictures—should hang in the curio room of an insane asylum.” This was overwhelmingly the response, certainly so outside of New York and small segments of the art world proper outside of America’s Front Door on the Atlantic.

Little recalled is that two-thirds of the works shown at the epochal Armory Show were by American artists (and not all of them avant-garde). The scandal of emerging European Modernism almost completely obscured the totality of the American art also exhibited.

America’s First True Moderns

Katherine Dreier herself as well as painter Marsden Hartley had made early abstract (and in Hartley’s case) Cubistic paintings right after the seminal 1913 Armory Show. Yet they almost never received any recognition for this work, then and indeed until much after the Second World War. Hartley, close to New York gallerist/photographer Stieglitz (another key figure open to the avant-garde) found himself reviled for pro-German sentiments after the U.S declared war on Germany in 1917. He reverted to modern figurative (or ‘objective’) painting and spent much of the rest of his life in self-imposed exile. Dreier, undaunted, kept promoting and exhibiting the European avant-garde in America despite extensive media hostility, even among art critics.

In the brief dawn of the ‘teens before the World War, there were Americans like the “Synchromists” (Stanton Macdonald Wright & Morgan Russel) who did some pure abstract work while living in Paris. But very soon, most American artists who dabbled in the more radical new styles returned to more marketable figuration, or at least alternated from mostly abstracted to more accessible work. Elements of Futurism, Symbolism, and with time, Surrealism were incorporated into many of these artists’ work. This included the Synchromists above, Georgia O’Keefe, Charles Demuth and Arthur Dove among others.

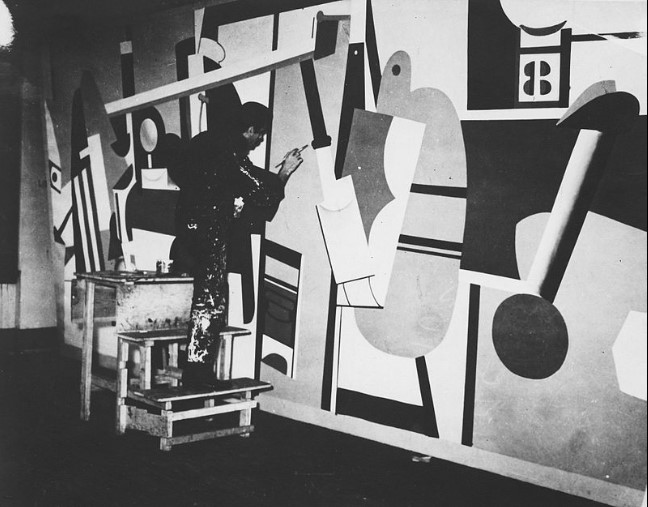

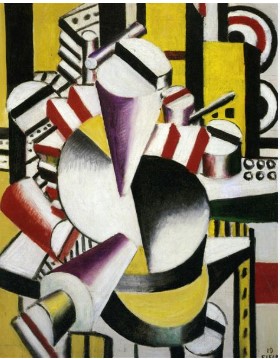

By 1920, Dreier had joined with Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and soon a few others (notably, collector and esthete Albert Gallatin) to create a Modern art collective: Société Anonyme (subtitled “A Museum of Modern Art”). One of Dreier’s exhibitions – an extensive show of Fernand Leger’s output – had a pivotal influence on one of the few American artists to move back to abstraction well before 1930:

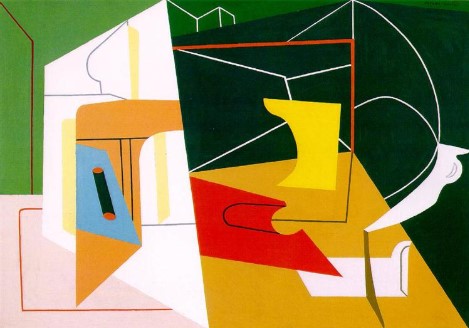

Stuart Davis (1892 – 1964).

Davis had spent the World War I years a self-proclaimed “committed Modernist” painting in his own variant of Cubism, after a kind of conversion experience upon encountering the Cubists at (once again) that famous 1913 Armory Show. Unlike most American painters, Davis seems to have somehow closely followed the Europeans in stepping partly away from Cubism after 1918, but not completely altering his style back to the representational. By 1925, following yet another bout of inspiration when he encountered Fernand Leger’s postwar paintings at a New York gallery show put together by Dreier and Duchamp, Davis tackled Abstraction from a new tack.

In his series of “Eggbeater” paintings, Davis found his own ‘voice’ (so to speak), turning still life subjects into almost entirely abstract, geometrical compositions. Yet there is something wholly American about these works. They seem to predict (or did they directly inspire ?) an entire genre of Mid-century American animation, a Minimalist version of which was sent up (lovingly?) by Mel Brooks in his Oscar-winning animated short film “The Critic” (1963).

There was more back and forth of creative figures and ideas between East and West Coasts in this period than is often recognized. Though Scheyer and Katherine Dreier worked in complete independence of each other’s efforts, and in effect were competitors for works, they knew a considerable number of artists separately that linked the two women. Not just titanic figures like Kandinsky back in Europe: Also artists in America.

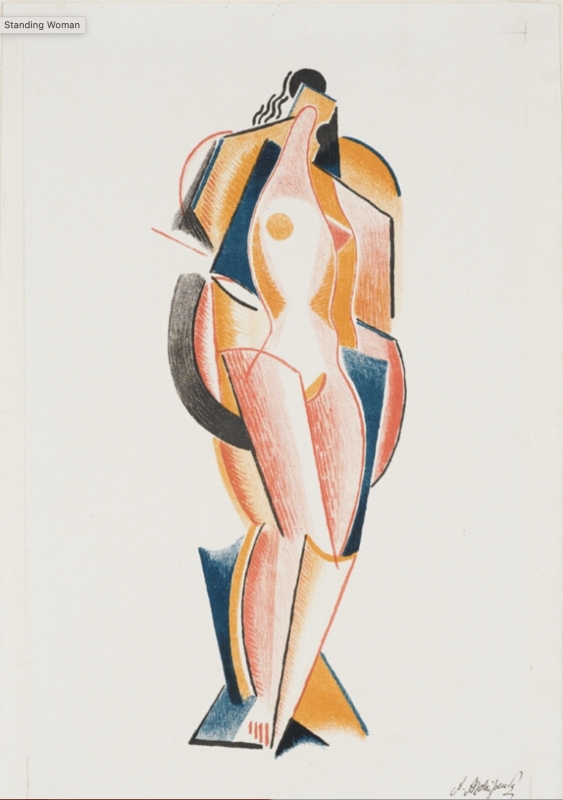

Both Archipenkos, for example: The sculptor and painter Alexander Archipenko, originally from Kyiv, Ukraine and his then-wife, Angelica Schmitz (Archipenko). Angelica was one of Scheyer’s first close friends in the United States.

Indeed, Angelica Archipenko actually accompanied Galka Scheyer when she finally left New York to relocate to California:

“Together (Galka & Angelica) visited Chicago, Denver, and Santa Fe before arriving in Los Angeles on 8 June 1925” (Quoted from “The Blue Four: Galka Scheyer and the Promotion of Feininger, Kandinsky, Klee and Jawlensky in California“, Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid by Clara Marcellán, the Curator of Modern Painting at the Thyssen.)

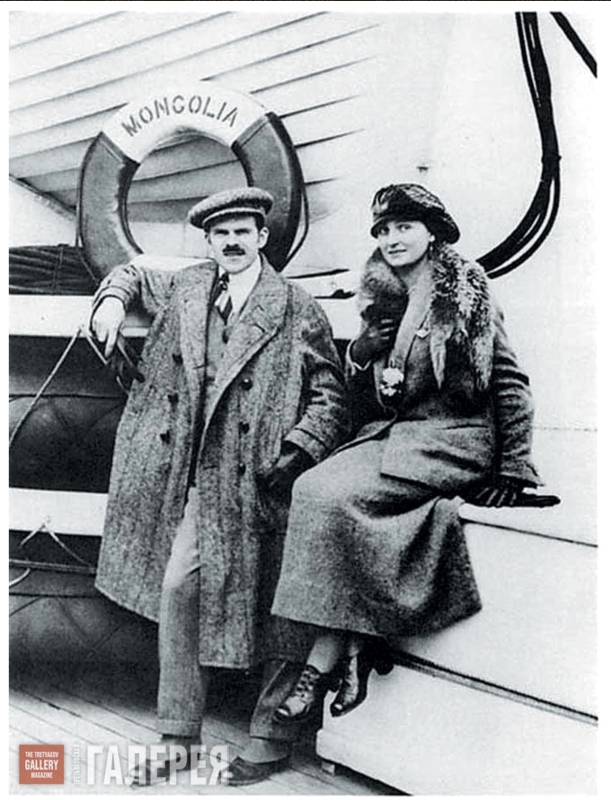

So Scheyer actually visited Los Angeles first with Angelica (also known as “Gela”), just before she relocated permanently to San Francisco. The Archipenkos themselves had emigrated from Paris to the United States earlier, in 1923, and were familiar enough with the country that Angelica could serve as a good traveling companion.

Even earlier, in 1921, Katherine Dreier’s Société Anonyme had presented a solo exhibition of Alexander’s work. Arriving in New York with an impeccable Modernist pedigree (Alexander had in fact exhibited with Picasso and Braque in the pivotal Cubist exhibition of the Salon des Indépendents in 1910, as well as the 1913 Armory Show), where they opened an art school, the Archipenkos quickly came to know some of the most important collectors of Cubism and early Modernism in the United States. And Dreier’s close connection with the artists continued: She sponsored another solo gallery show for Alexander at New York’s Anderson Gallery in 1928 simply titled “Archipenko.”

Art Evangelist to the East Coast

In total, though in its last decade rather pushed “off stage” by the new Rockefeller-supported Museum of Modern Art from 1931 forward, Société Anonyme sponsored 80 exhibitions before it essentially shut down in 1940. Collaborator Albert Gallatin hadbroken off by himself much earlier, in 1927. Gallatin then began exhibiting his own collection, primarily at New York University, through 1936. Gallatin’s “Gallery of Living Art” was a favorite of artists Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston and Robert Motherwell, among others.

Dreier soldiered on without him. In 1926, she purchased her first work by Piet Mondrian, Painting I; and then arranged its New York exhibition as part of a large exhibition she had a pivotal role in arranging at the Brooklyn Museum – the first such showing of Mondrian’s work in America. As mentioned above, she had a crucial role in Léger’s first U.S. solo exhibition even earlier.

Katherine Dreier not only arranged museum and gallery exhibitions in precisely the indefatigable manner of Galka Scheyer. She also taught, lectured and wrote (her Three Lectures on Modern Art was at last published in 1949, three years before her death).

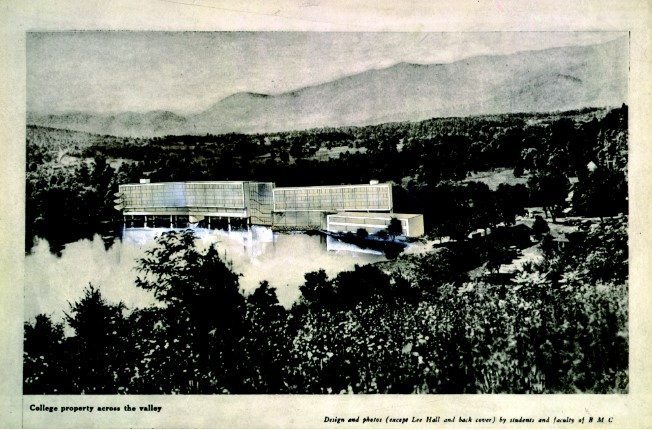

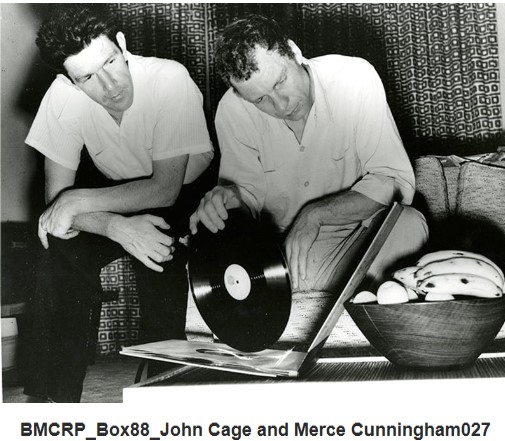

Dreier did not confine her efforts to the environs of New York City, for that matter: “During the 1920s and ’30s she lectured widely on modern art, including talks at the Berlin Bauhaus (at the invitation of Vasily Kandinsky) and Black Mountain College (with Josef Albers).” Black Mountain College (in existence from 1933 to 1957) near Asheville, North Carolina is where Galka’s young friend John Cage went to study, and where he met his frequent collaborator, choreographer Merce Cunningham.

The Reaction Against Abstraction In Painting After 1918

Even in Europe, the first wave of abstraction represented by Cubism, Kandinsky and Klee receded following the end of the Great War. This retreat from pure abstraction was by no means a solely American phenomenon. The early 1920s has been dubbed by art historians the “Recall To Order” (le Rappel à l’Ordre). The term itself comes from an essay by Jean Cocteau, dedicated to Picasso’s figurative and mythic paintings, rather than an assault on his Cubism.

It should be acknowledged that Modernism is not a single uniform movement, despite the inevitable tendency to narrate its history as a consistent march to a pre-determined conclusion. The influence of Freud, Jung and psychoanalysis was enormous, and suggested a reinterpretation rather than wholesale rejection of Classical myth as inspiration for fine art – even though depiction of mythic subjects had been continuous in Academic painting, as it had been in Europe since the High Renaissance.

To completely stop painting portraits, the human figure, still life and landscapes was not the desire or destiny of most Modern artists; nor should we automatically devalue work that remains recognizably within these genres. Indeed, of Scheyer’s “Blue Four” only Kandinsky himself completely abandoned these subjects, purely painting in the abstract mode from 1911 to his death.

Theosophy, religious belief, generalized mysticism and elements that later coalesced under the still-somewhat pejorative label of “New Age” since the 1960s were also enormous influences on some early Modernists, for that matter.

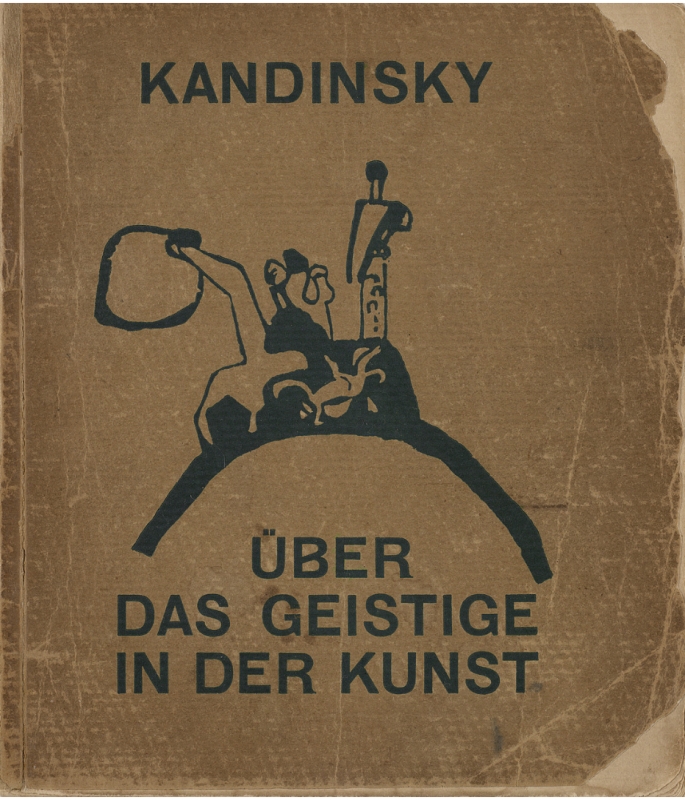

For example, once again, Wassily Kandinsky: His manifesto on abstraction was entitled “Concerning The Spiritual In Art” (published in 1911). The abstract master had to explicitly disassociate himself from the rather cult-ish Theosophy movement (though it had been an influence on him) within a short number of years after this publication.

Those who chose to devote themselves to promoting the new currents in art had varied opinions on the promise and purpose of Modernism themselves. What they shared was a repudiation of the late Academic mindset, that by 1900 had become entrenched at American art schools (notoriously at the National Academy of Design, headquartered in New York.)

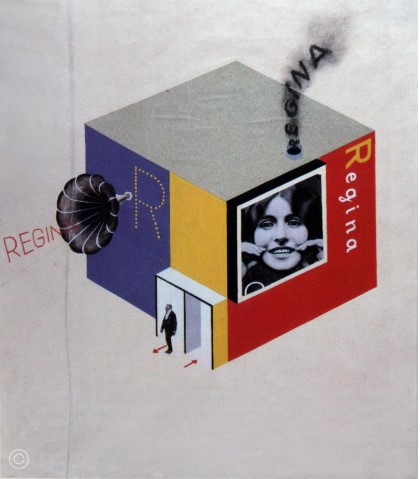

Many Modernisms

Art historian Michael J. Lewis has defined the loosely affiliated Modern Movement in America this way: ” [An] avant-garde…which touched art, music, literature and dance, each of which aspired to the same radical emancipation from traditional structures of form and authority.”

Notably this list does not include architecture. For a simple reason: In his masterly survey “American Art and Architecture” (2006), Lewis immediately moves from the arts that followed European models to “the practical art of architecture…[in which] American experiments in skyscrapers and steel construction had long outpaced Europe [by 1900].”

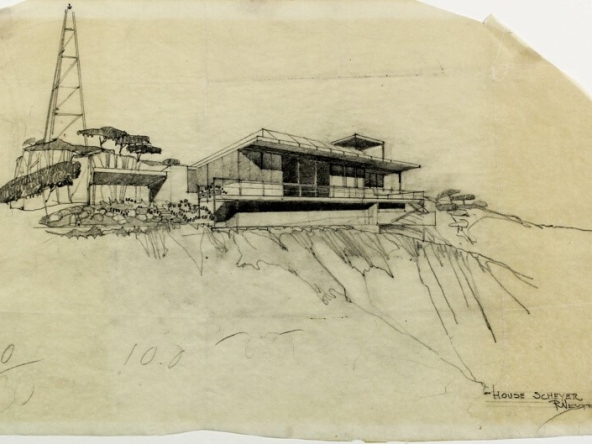

Lewis correctly identifies the development of Modern architecture as an America-to-Europe, yet also Europe-to-America “cross-fertilization.” Whose pivotal, home-grown figure was (“certainly the single most important artist in American history“) Frank Lloyd Wright.

Yet the convergence of a mentality that embraced interconnected ideas about Modern art and architecture took decades, and it developed in California well before it arose in the rest of the United States. Wright himself was a great outlier, who lived through the long period when American architecture became steadily more Academic, less Modern, more Beaux-Arts and more historicist, and often lacking any identifiable national style or signature whatsoever, from circa 1893 to about 1920. And from then on, only in a very gradual retreat up to the entry of the United States into world war in late 1941.

Hilla Rebay’s ‘Non-Objective’ Art Crusade

With the third apostle of Abstraction to the Americans, abstract art, Cubism and Kandinsky’s path “to the spiritual” finally culminated in direct patronage of American Modernist architecture. The long, fertile, sometimes controversial career of artist, curator, publicist and polemicist Hilla von Rebay (1890 – 1967) culminated in the drawn out struggle to build Wright’s last masterwork, the Guggenheim’s home on 5th Avenue in New York.

Well before the onset of the Depression, Dreier had championed and collected both Kandinsky and Mondrian. The two European artists separately encouraged Dreier to meet Rebay in 1930, after her pilgrimage with Solomon Guggenheim to Europe to meet them earlier that same year. (This was also when Scheyer found her “exclusive” representation of the Blue Four down-sized to California at most, rather painfully, one surmises). Following this meeting, Dreier became close to Rebay; and thereby a significant influence on Rebay’s work for Solomon R. Guggenheim’s burgeoning collection of great Abstractionists.

Rebay was yet another 1920s émigré, arriving in New York in 1927 from Berlin. Her trip to the Bauhaus in 1930 with the collector, during which she introduced Guggenheim to Kandinsky and his work, was the catalyst for a treasure-trove, the Guggenheim collection of abstract Modernist work. Completely. (https://www.guggenheim.org/about-us/history/hilla-rebay).

Indeed, Rebay and Dreier had studied painting at the same time in pre-World War I Munich (!), though they don’t seem to have met before 1930, as far as is known.

The incipient New York Museum of Modern Art’s exhibitions after 1930 still garner most of the attention in narratives of the origins of Modernism in America (a role critical in spreading appreciation of modern architecture. Whereas it was far from alone in regards to the visual arts more broadly). A rivalry between the Modern and the early Guggenheim ended in a clear victory by MOMA, and over all others really by 1945, if not earlier.

Even so, this telling of art history in America simply ignores Dreier’s role in earlier exhibitions as well as Stieglitz’s even earlier 291 Gallery shows; and the exhibits curated by Rebay, including for the “Museum of Non-Objective Art” (its name before it was re-dubbed The Guggenheim Museum).

Or at Gallatin’s collection housed at NYU from 1927. These exhibitions were typically more adventuresome shows that concentrated (sometimes solely) on works by artists like Kandinsky. This kind of solo show was not to be found at Alfred Barr’s institution before circa 1940; more outré Modern art usually appeared well-leavened with figurative work in the exhibitions of the still-homeless (pre-1939) early MOMA.

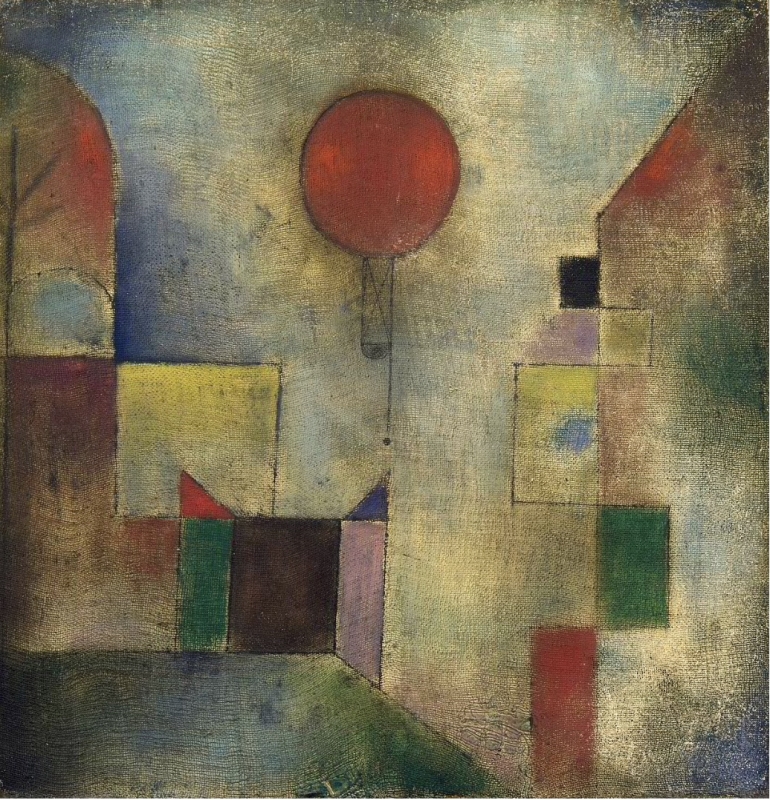

MOMA carefully bracketed abstract work with representational work, often by the same artist, in many of its early shows. As in its 1930 exhibit “[painter Max] Weber, Klee, [Sculptor Wilhelm] Lehmbruck, Maillol.” An idea of the public reception for largely abstract or overtly modernist painting at the time can be found in the New York Times’ review of that show (“The Two Poles of Art“, a very insightful title) by art critic and historian Elizabeth Luther Cary, published March 16, 1930.

Cary began by warning that: ” … conservatively-minded viewers will suffer a quite a good deal at the hands of Mr. Klee and Mr. Weber….” That Cary, herself an expert on William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelite Rossettis, and born in 1867 (!!), then praised Klee’s “gayety, childlike imagination [and] mature skill” – yet perhaps reluctantly devoted the vast majority of her review to the more figurative sculptors Maillol and Lehmbruck – is telling. All of it shows how large yet remained the veritable abyss in appreciation between a very small group of art-world insiders and the general American public.

A “Colonial Cringe” ?

Long, long before the seminal and controversial 1913 Armory Show, would-be American artists had habitually wrestled with a demoralizing sense of provincialism. From the very first Colonial-era origins of painting portraiture, comparison to Europe’s best was usually… uncomfortable and worse.

Overshadowed by the European Old Masters, American painters often seemed to have only the choice between outright imitating European models or rebelling against whatever was in vogue across the Atlantic. Even when American artists rejected the inevitable comparison, the broader public never stopped viewing Old Europe’s art output as superior to any home-grown version, so much of the time.

And while most American interwar artists absorbed influences from Cubism and early abstract painters in the decade after the 1913 Armory Show, partly due to Arthur Stieglitz as well as Drier’s (among others) early advocacy for Modernist painting… even so.

In the United States, there remained a stubborn insistence (at least for those who purchased art, with very few exceptions before the 1930s) on always and only painting at least partly recognizable figures, places and things.

The exceptions before 1934 exist, many cited here, but they were isolated figures (there might be abstract elements as in Peter Krasnow’s depiction of Galka Scheyer lecturing. But with easily recognized human figures aplenty; and no need to read a label to have a sense of the subject).

Significantly, of all the visual arts in the United States, it is photography that most historians of the arts see as the most vibrant and innovative American interwar medium. In the 1930s, the United States became the principal world center of both art and documentary photography, and here were developed multiple innovative techniques and styles. Indeed, several of the most noted painters of the period employed not just the brush but the camera. And were indebted to photography for inspiration.

More conservative still in their public statements, some of the most famous American painters of the 1930s denounced the entire Modern movement and all thing European to the mass media (most famously, painter Thomas Hart Benton.) Despite being subtly (or not so subtly) influenced by recent European predecessors and the Americans who had taken up (even if briefly) some of their ideas.

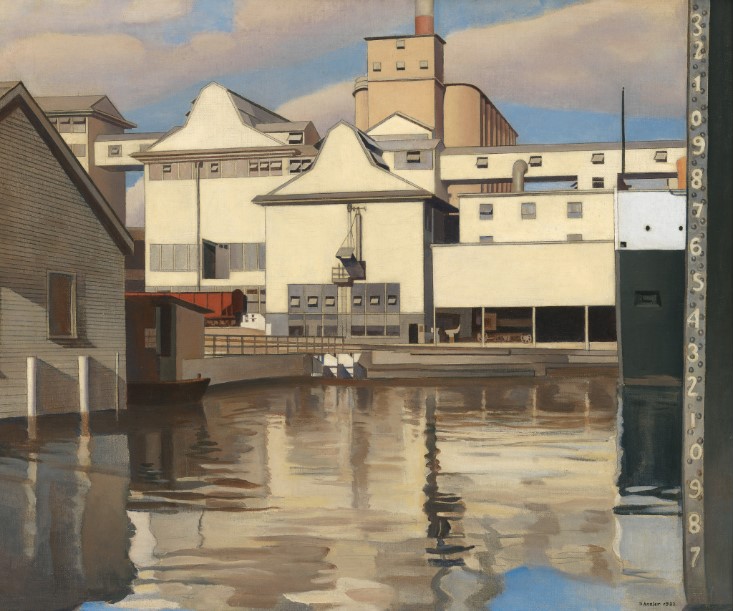

The more Modern-inclined “Precisionists” (most famously Georgia O’Keefe & Charles Sheeler) had dabbled with cubistic landscapes, yes. But they nearly always painted objects that remained clealry recognizable (Sheeler actually both photographing and painting the same subjects). Were Americans not just excessively materialistic and money-mad, as European visitors and critics had so often, monotonously, charged; but perhaps inherently incapable of appreciating anything not within their lived, everyday experience?