In 1969, Richard Neutra and his architect son Dion were asked by curators at the Smithsonian to record his thoughts about his career, architecture and philosophy. The audio recording would accompany a slide-show of his buildings, a key part of a retrospective exhibit held at the “Institution” located on the edge of the Mall in very heart of the U.S. capital.

Often called “America’s Attic”, the Smithsonian is an encyclopedic collection of Americana—the culture, history, memories, technology, consumer products, and articles of daily life in the United States. It is both a museum and a kind of national Pantheon for American lives worth remembering. Lives that had impact. This must have been a deeply gratifying moment for the Neutras, father and son: “The Ideas of Richard and Dion Neutra” marked an official seal of the lasting influence of Neutra’s architecture on Richard’s adopted country.

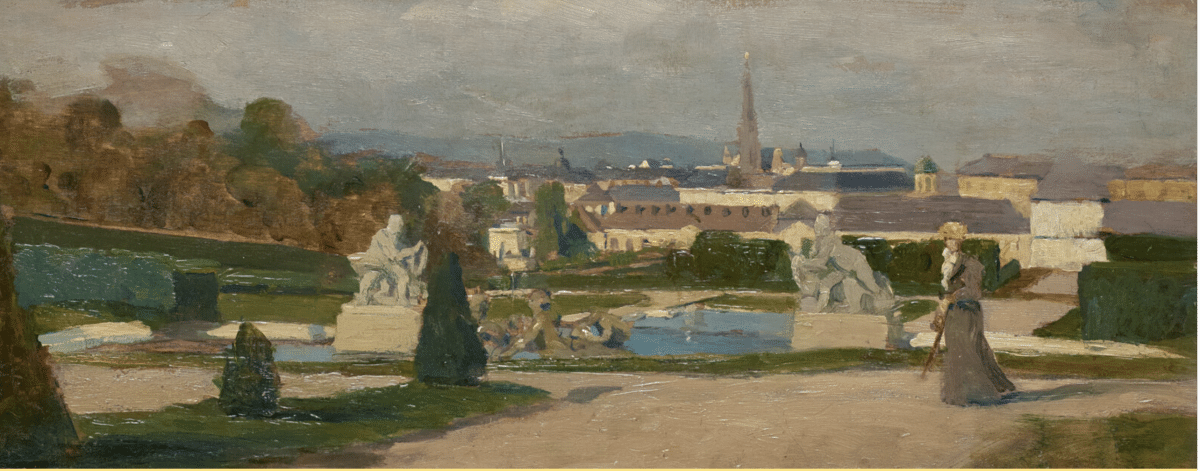

The immigrant born in Vienna in 1892, only arriving in the United States in 1923, had become an icon of the New World. As his heart condition was worsening, this was to be the last year of Richard’s life; his son, Dion, was to continue expounding their ideas for nearly a half-century more.

In the year of the Moon Landing, the Neutras had some deeply considered thoughts about the “machine-civilization” that seemed to have reached a glittering zenith in that year, literally reaching into the once-unattainable heavens:

San Gabriel, CA 1972.

[Richard Neutra speaking:]

“I have so often wondered, where do we go from here?”

“Unless heroic efforts are made, and systematic insights used, we will simply have more traffic, more smog, more noise and more daily monotony.

What will happen to the man, woman and child who must live surrounded by this man-made, chaotic and statistically regimented environment? What will happen to them? Will he be like a fish out of water, stranded in a hostile milieu of his own making? “

TECHNOLOGY AND THE HUMAN ENVIRONMENT

Modernism in architecture has often been told as the story of a necessary embrace of the reality of the 20th century, the century in which technology and the machine revolutionized nearly every basic fact of daily human life in the “advanced countries.” And as predicted, the rest of the world has followed the same path in at an accelerating rate.

Yet this was true first and most profoundly so in the United States in the years before and (especially) following victory in the Second World War. From the most mundane daily needs of bathing, cooking, cleaning to heating our houses and cooling ourselves off, all of daily life was being transformed by the installation of the appliances known as “mod cons.” By just before 1960, the arrival of reliable jet-fuel powered airplanes was soon to put nearly all the cities on Earth within 24 hours’ travel time of each other, an astonishing acceleration.

But in his last year of life, far from being triumphant, the visionary architect Richard Neutra was concerned with something deeply troubling: Our divorce from the natural world and the milieu in which we, as human beings, had anciently evolved.

A gap that was widening, not closing. Despite – or because of? – our machine-made miracles. Was the ever-rising U.S. Gross National Product a boon without drawbacks? That booming growth financed ever-more sophisticated space-attaining missiles; and ever more gleaming, more luxurious air-conditioned cars, to be sure. And all those new cars required wider and longer and faster and… louder…more smog-inducing expressways…more airports to drive to. And more and yet more jet planes roaring through the sky to get from boom town to boom town. The bone-rattling thrill inside a 707, that early behemoth the 747, or a DC-10 as they took off wasn’t quite the rush of an Apollo astronaut on an Apollo rocket launch…but it was as close as most of us could come.

Think for a moment of Vienna and the Austrian countryside around it before World War I – the milieu in which the young Neutra grew up. The piercing whistle of a train’s steam engine was still less often heard than church bells then. Nearly everywhere. Those who didn’t work in factories were mostly unused to man-made noises that made it impossible to hear the person standing next to you. From the deafening artillery barrages that Neutra himself endured in the First World War; to the sound of horns honking constantly on streets newly clogged with automobiles and trucks; to the ever more commonly heard whine of airplane engines and roar of jets, a new and obnoxious god – Noise – seemed to then take over, advancing hand-in-hand with wealth and ‘Progress.’

And so, with all their obvious advantages, were these changes truly enriching our lives? Or was much of this transformation also beating away at all of us, man, woman and child, with more and more noise, more distractions, more pollution, more alienation from our most essential and natural needs?

FUNCTIONALISM OVER ANTHROPOLOGY?

The ambition of Modern architects to solve the problems of human environments (and of our cities in particular) via enlightened and systematic new solutions had already started to seem in 1969 as a well-meaning but obvious failure. Urban renewal in the United States was destroying neighborhoods, disproportionately inhabited by immigrants and racial minorities, and replacing them with monotonous tower-blocks mostly devoid of shops, small businesses, and services.

Suburbs were mushrooming, but largely via purely speculative development and with nearly zero provision for transportation other than the lone individual in an automobile. (Where rail and streetcar networks had formerly connected suburbs to urban centers all over the West, Midwest and South, now many were closing down or withering away as in Los Angeles, Detroit and St. Louis. And many other cities).

Critics, at first unheard, were not wrong in denouncing many of these “Renewed” districts as anti-communities: Their relocated inhabitants once shaken loose from familiar surroundings, the signs of social alienation multiplied. In the same year of 1969 urbanist Jane Jacobs was profiled in the New York Times. More than a decade before she had already observed that Modernist city-planning, methodically dividing housing from shopping, retail from offices, offices from factories had created new districts that were “neither safe, interesting, alive nor good economics for cities.” Most of all, they were often un-walkable or wholly oriented to automobiles. Deserted by pedestrians, some became notorious for street crime after dark.

Meanwhile, liberated from living close to their factory or office by cars and freeways, most Americans now could live far from their workplaces and were little attracted by the “renewal,” even when in most respects splendidly designed. As with Mies van der Rohe’s beautiful yet profoundly anti-urban Lafayette Park next to Downtown Detroit erected in the mid to late 1950s. (And built on the site of a brutally razed African-American neighborhood — see link below for more). Many Americans abandoned cities entirely for life at the suburban fringe, wherever highways reached.

Demand for glass, concrete and steel was spiraling to unprecedented quantities; ever more asphalt for parking and driving on was laid down, higher skyscrapers erected, vast subdivisions built up, larger supermarkets erected, bigger shopping malls constructed—building was going on everywhere in booming 1960’s America.

But were these structures actually addressing our most important needs, or merely facilitating more consumption, even when some of that consumption – more Pop Tarts, anyone? – was actually, as a small group of heretics had already come to realize in 1969, harming us.

Without going any deeper here into the Neutra world-view of “Biorealism,” we can recognize that misgivings about Progress – especially in Old Europe – were far from unprecedented. Even if warnings on this score were often unheard or dismissed with a chuckle or two by the “mainstream” of American society in the years right after the Second World War.

It hardly seems that we have made enough of those “heroic efforts” that the Neutras called upon us to make in 1969. Yes, the Clean Air Act was put into effect; yes, most of us try to sort out “recyclable” materials, even though a great deal of it isn’t and won’t ever actually be re-used. But just how many sustained and complete efforts to overcome the problems of our shared environment have we attempted? How diligently have we taken action to reduce the ever-increasing stressors on human health: Bad food; deafening noise; toxic chemicals, fuels and products; inadequate physical activity; lack of rewarding social relationships; and often obscuring those needs, all the throbbing, distracting chaos of modern life, intensified by the incessant pings of social and other media on our phones?

Without any pretensions towards heroism, here we hope to highlight those physical environments, and the interventions possible to them, that serve what “we [as humans] do, and how [we] socialize while serving [our] health and well-being as well as delighting [us.]”

Not sheer inflated scale, but fitness to purpose; not grandiosity but integration to good air, sunlight and living nature; not newness per se but lasting delight from the most thoughtful efforts to give us beauty and utility in our daily environments. These perhaps not so often heroic but sincere and true examples may help us to cope and even thrive despite our problematic, regimented and frequently bewildering urban environment.

Further Resources:

The Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design

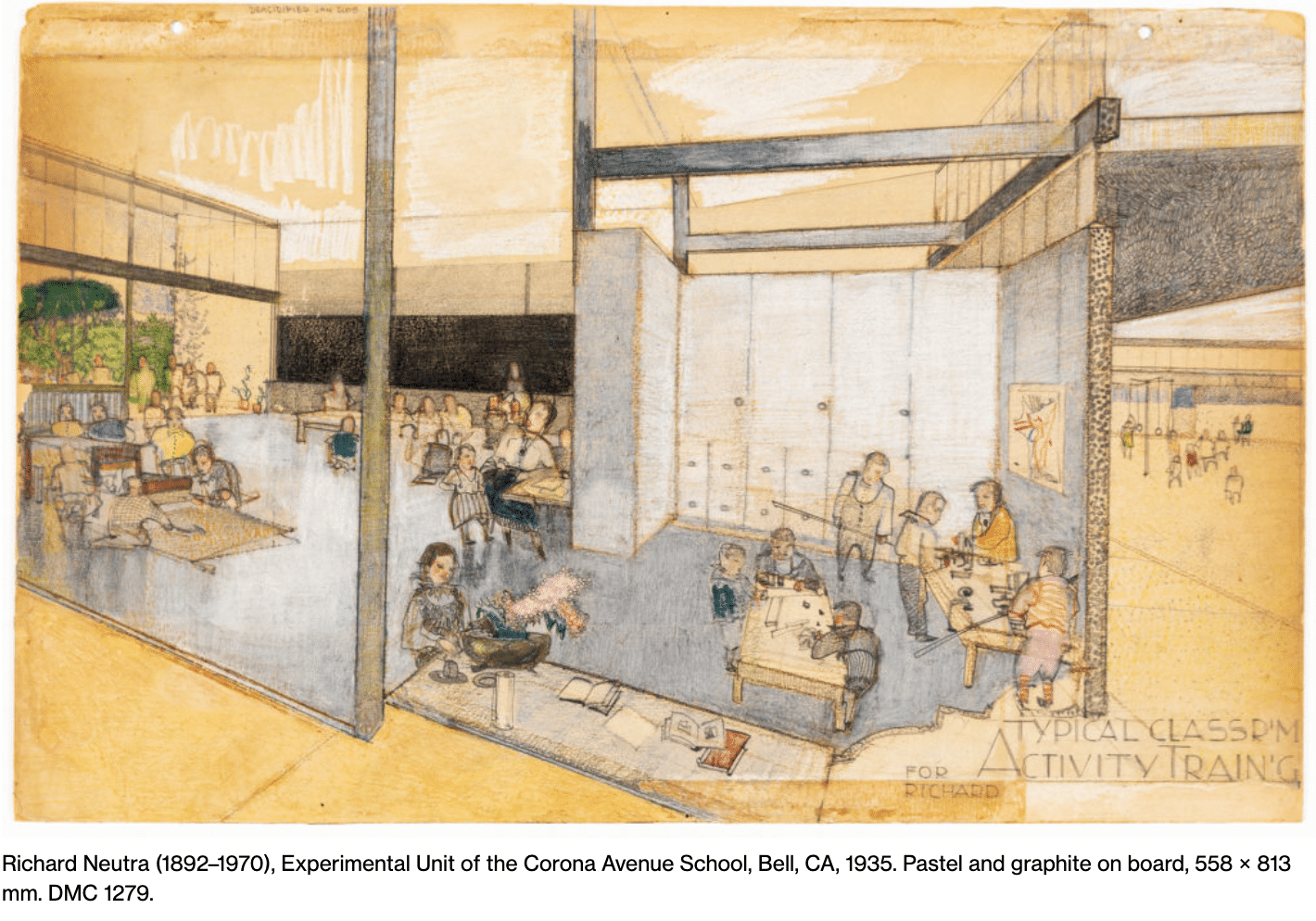

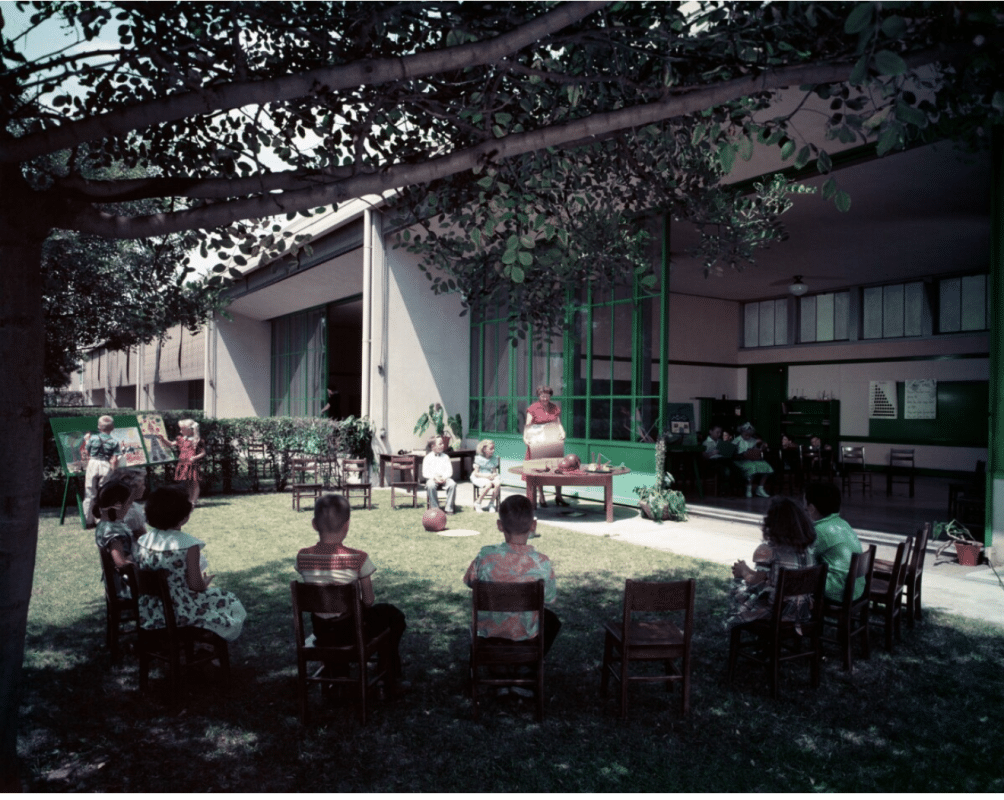

Fresh Air and Outdoor Learning at the Corona School

American Idyll – The Roberts House, West Covina, CA

Bewobau Siedlung Quickborn, 1963-64 (near Hamburg), Photographer Iwan Baan