Whatever the downsides of the Social Media age we are living in, one of its advantages is that it has never been easier to see what is being designed and what is being built right now. On LinkedIn; on architects’ websites; and on Instagram, in particular. Instagram offers a nearly inexhaustible trove of images of new architecture, design and furniture. Accounts curated by professional designers, furniture manufactures and retailers, architects and architectural aficionados abound.

When Shelter Magazines Were Practically Everything (pre-2010)

Not all that long ago, subscriptions to magazines like Dwell, Architectural Digest and Wallpaper were the main source of information in the United States for non-professionals with at least a passing interest in modern design. And for even longer, many of us mostly learned about great Modern houses through newspapers’ full-color “Sunday magazine” supplements. The New York Times, print or online, with its T Magazine since 2004 was and remains a national platform for designers. These “old media” publications covered both new and already well-established figures in architecture and interior design in both the United States and Europe.

(A great deal more was available to discover if one browsed and purchased multilingual European publications like the storied Domus, first published in 1928.)

There was of course much more media coverage in total, but searching out the latest creations by architects in Mexico, Israel, Argentina, Iran and Taiwan was much more difficult than it is today. (Wallpaper was a standout in looking more globally than had been true before the year 1996 — at least for publications readily available in the U.S. The pricey Monocle created by that publication’s founder is even more globally-oriented).

Social Media Uber Alles?

Today, anyone with a smartphone can easily find images of new work that is excellent and original all over the planet. Most “starchitects” can be directly “Followed.” Dozens of Instagram accounts present daily full-color images of the classics of early and mid-century design that have had the most influence on today’s Modernism. Others show historic architecture around the planet, from Japanese Buddhist temples to Mayan pyramids to St Peters Basilica in Rome.

Those born after 1980 may well never have cracked open a book on the history of architecture that had no color photography or illustrations whatsoever — whereas the first book your author here can recall reading on the subject, Prof. Eliot Steen Rasmussen’s “Experiencing Architecture” published in 1964, had a single color illustration. On the cover.

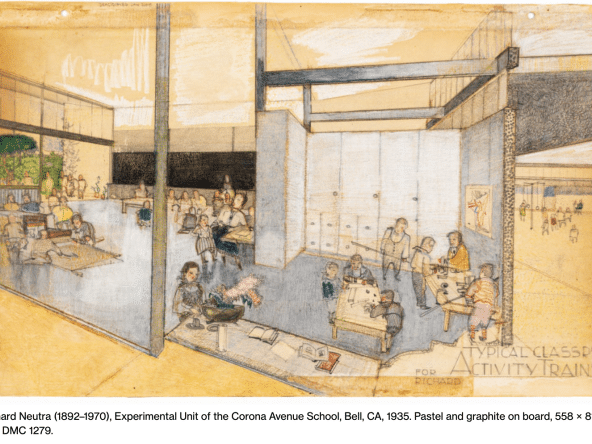

Indeed, future posts will inquire to what extent the lack of accessible color photography of the earliest International Style villas of Le Corbusier, and the handful of Bauhaus Masters’ houses, only restored in this century from the unrecognizable state they were put in after 1934, distorted perceptions of the views of early Modernist masters on color in interior design.

‘Minimalism’ is far more recent than we often realize, though with roots that go into the mid-century.

Aside from the ever-growing ranks of glossy and expensive full-color books on past masters like Le Corbusier or van der Rohe, the internet today links all of us to a cornucopia of architecture past and present.

Browsing through this suddenly accessible universe of possibilities directly, rather than through the filter of editors at well-known shelter magazines, is empowering and a source of delight for many. And yet.

None of us can visit in person all of these fascinating structures in cities all over the United States and/or throughout Europe, without most of a lifetime devoted to just this one goal and nothing else. And if we consider the whole globe, the task is even more impossible.

So instead, we ask readers to take a little time to think over buildings they may already have some familiarity with, eyes and minds open. Focusing in on a theme, an idea or two, and just how buildings we admire came to be conceived should enrich our understanding.

We will reach out directly to those working right now to create great, pleasing, healthful and effective new buildings. And those fighting to preserve the best work of the past: Recent, not so recent and remote.

The Goal of Design For Living

Here we will politely suggest readers think again about both past and current design figures whose names they have heard of (often); or about a body of work some may already know well. To take a moment to ponder and even question what everyone seems to think–and why. Not just keep scrolling to the next beautiful image.

We don’t expect perfect agreement with some of the opinions that will be expressed in posts. If an error is made or a generalization pushed too far, corrections are solicited and welcome.

Great efforts will be made to check facts, link to sources and account for views that may differ from the posts blogged under the title Design For Living. If lively debate is fostered by posts, as long as it is conducted respectfully, we couldn’t be more pleased.