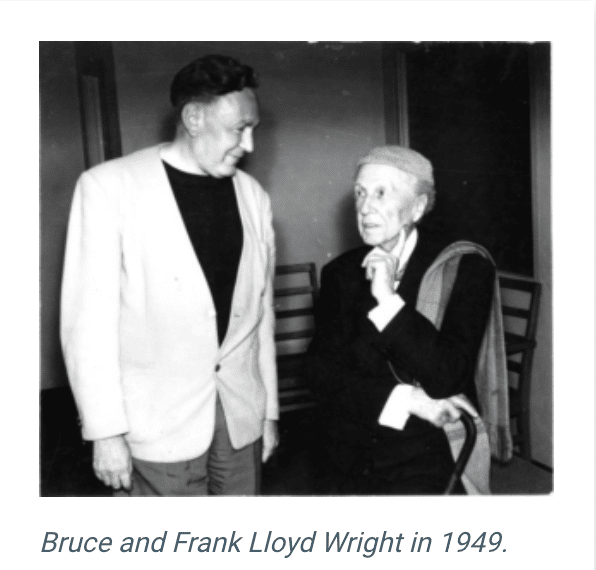

Bruce Alonzo Goff (born 1904, died 1982) never studied directly with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin. East or West – Wright’s architecture school was largely developed in Scottsdale, Arizona (where until recently it was still headquartered.)

Unlike John Lautner, who completed his degree at Taliesin under Wright’s direct supervision.

But the teen-aged Goff apprenticed to a leading Tulsa architecture firm at the age of 12 (!!) even younger than Wright himself when he began as a draftsman for Adler & Sullivan in Chicago. Goff did then write to his heroes Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan when he was offered a chance to travel to Paris to study at the renowned École des Beaux Arts. And they both responded! Replying with appreciation and encouragement – and advising him, in Wright’s words “If you want to lose Bruce Goff, go to school.“ A teenage prodigy like Wright himself, Goff was well-known in his lifetime to architectural historians and critics. And to many practicing architects who also looked to the Wrightian tradition for inspiration.

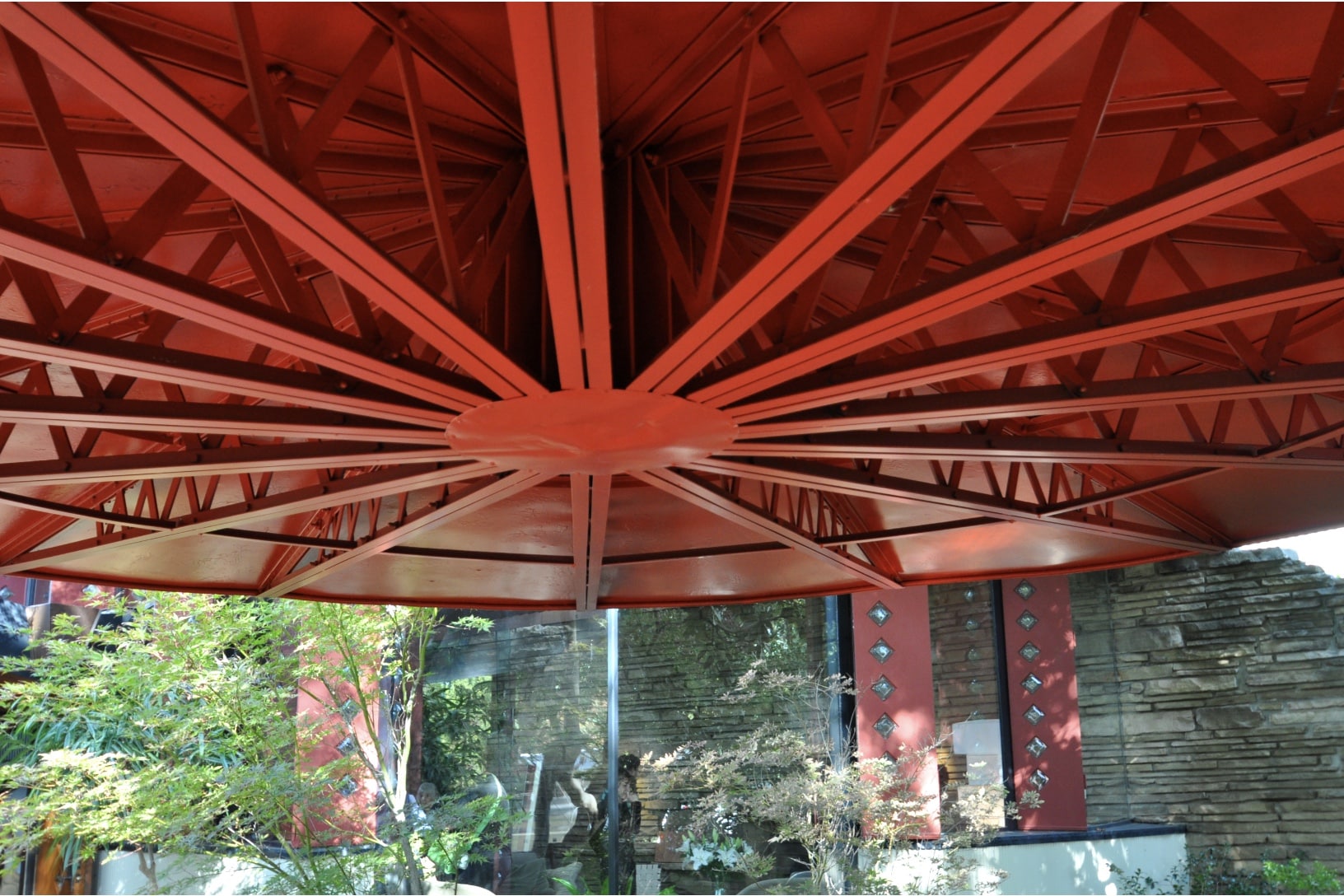

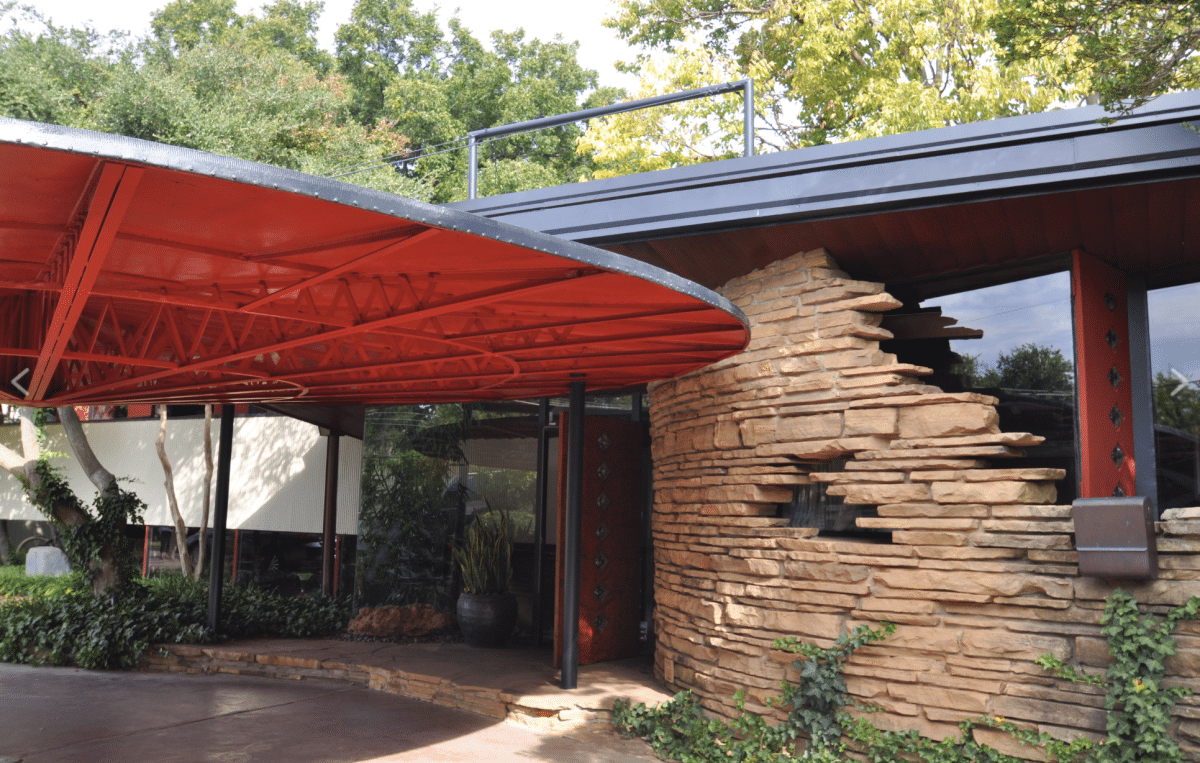

But in 2023? Relatively few seem to know his work outside of architecture graduate schools any longer. Worse, one by one, several heedless new owners have demolished several of his greatest houses (as with his Price House above). Rather than restore them now that five+ decades have passed. As could only be expected after a half-century, significant repairs are to be expected with many of Bruce Goff’s designs. They require new architecture-loving owners unafraid of construction and contractors. Outside of central and west Los Angeles & the environs of Seattle, San Francisco, New York and Boston, how many such persons are to be found?

The New York Times has in our decade published in T Magazine about this neglect of Goff, truly an architect of considerable genius — asking in the sub-headline “Why Has He Been Forgotten?” (2018).

Sometimes called an “outsider architect,” Goff was self- and on-the-job trained, and most of his over 500 designs are scattered from the environs of Tulsa, Oklahoma to outside of Chicago. (Goff did design a handful of California houses, including the Al Struckus House in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, sold by Crosby Doe in 2002). Overall, Goff’s surviving built work largely resides in “flyover country” far from the main media centers of the United States.

And that still matters, even in our Social Media century.

Two Outsiders, Noticed But Far From Lionized

Yet there is an interesting comparison to be made between Goff and the coastal, Los-Angeles based John Lautner. Both lacked connections to the academic Modernist orthodoxy and professional networks of the postwar architectural establishment that solidified after 1945, with its great early centers at USC, Harvard, M.I.T., Yale and Illinois Tech. Nor did either man teach or study at the smaller ones like North Carolina State; Cranbrook Academy outside Detroit; or with Harwell Hamilton Harris at the University of Texas at Austin in the 1950s.

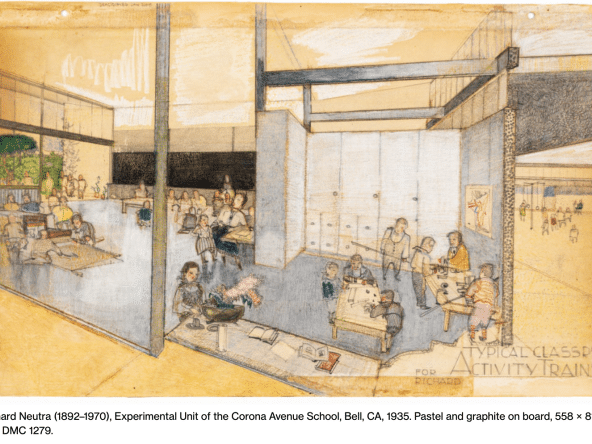

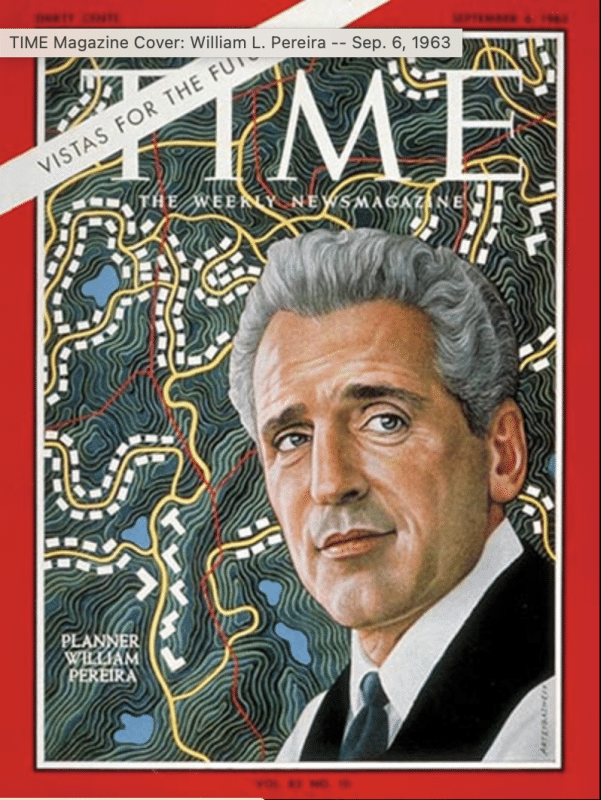

Certainly, neither were even considered for a TIME magazine cover, an honor Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, and Philip Johnson received; nor given the lengthy profile pieces that made sure ‘middle-brow’ America knew who icons Eero Saarinen (1956), Le Corbusier (1961), William Pereira (1963) and Buckminster Fuller (1964) were.

The attention Goff did receive in mid-career was, as Washington Post architecture critic Benjamin Forgey has written, “double-edged. There was ridicule in the appreciation, and vice versa.”

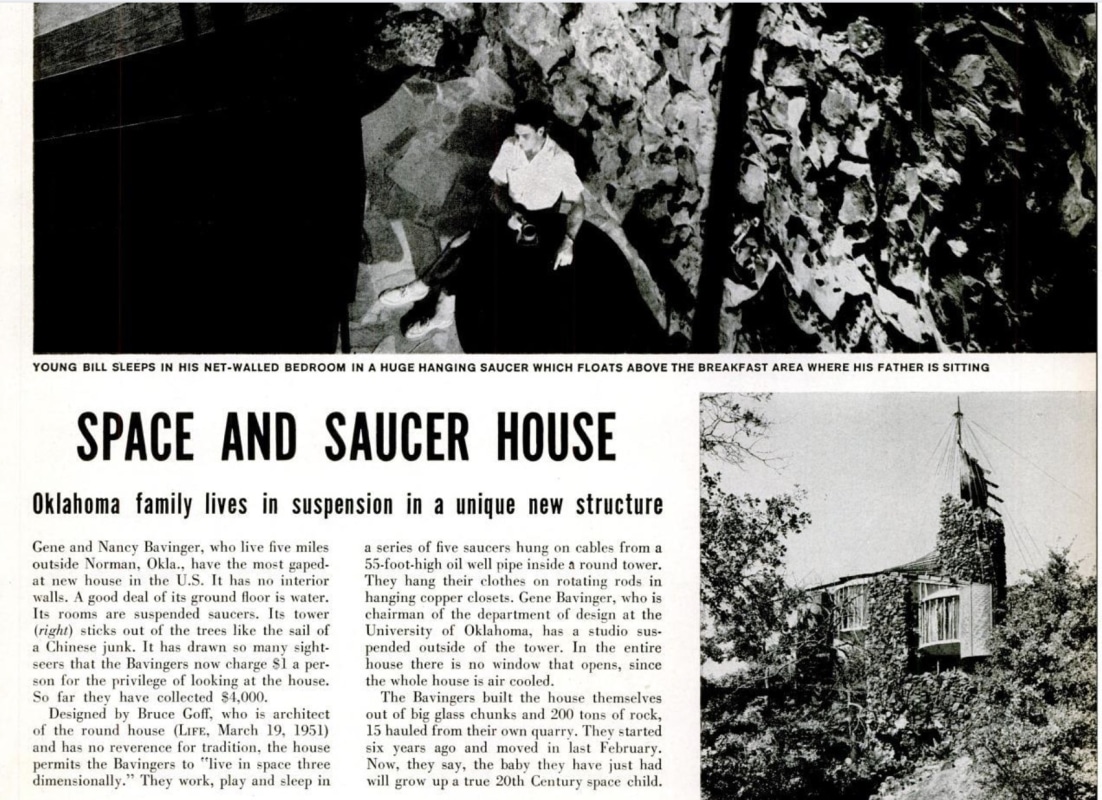

LIFE magazine took notice of Goff’s Ledbetter House finished in 1948 in Norman, OK, reporting “Consternation and Bewilderment in Oklahoma.” Presented as curiosities as much as architecture in the LIFE articles, the Ledbetter House — and again, with an article on the Ruth and Sam Ford House in Aurora, Illinois — Goff’s houses came across a bit like Route 66 attractions. On par with giant fake wigwams advertising motels or the “World’s Largest Rocking Chair” (now demoted to Second Largest, and still to be found in Fanning, Missouri.)

Half-mocking the coverage may have been, but it was national news. Some may have been motivated to seek out the architect; especially those who sympathized with the Ford family, who put up a sign in front of their Bruce Goff residence that stated: “We don’t like your house either.”

East Coast “Functionalists” Versus All-American “Organicists”

A half-forgotten part of the story of the mid-century Modern movement is the controversy that any kind of modern house stirred up all over the United States. When the architect was a European, the subtext of press mockery was usually restrained (“European” as an adjective in the United States – still! – is taken as a synonym for high-quality and luxury, stubbornly so).

Home-grown talent, in contrast, could be held fair game for disdain. That LIFE’s descriptions of Goff-designed houses included more than a hint of Rube Goldberg-esque bemusement allowed editors to showcase the new – while simultaneously flattering the prejudices of readers who viewed Modern houses as curiosities for crackpots, at best. Goff “has no reverence for tradition” LIFE informed its readers.

Was this praise or criticism? Deliberate ambiguity, more likely.

Both Goff and Lautner had little sympathy or praise themselves for the European icons of the International Style – Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier or Gropius – as individuals, and were indifferent (at best) to their built work in the United States. But at least Goff was profiled by the New York Times’ architecture critic, Ada Louise Huxtable. Huxtable reviewed a New York gallery retrospective of nearly 60 years of Goff’s wildly inventive architectural practice, on February 8th of 1970.

Even though Huxtable’s praise-filled review of Goff’s lifework was given the mocking (and not-very-subtly homophobic) headline “Peacock Feathers and Pink Plastic” by anonymous New York Times editors.

The Times, the nation’s “newspaper of record” seems to have barely taken any notice of John Lautner (except for his ‘Flying Saucer’ Chemosphere) whatsoever until 1987, in a brief notice of an exhibit by critic Joseph Giovannini. The paper finally published an article solely on Lautner – in the edition of June 14th, 1990. Only a mere 50 years after Lautner completed his first independently designed house for himself, in Silverlake. A mere 29 years after the completion of the iconic Malin Residence (“Chemosphere”) and…and…how was this possible? In retrospect, a damning neglect by New York-centric Big Media indeed.

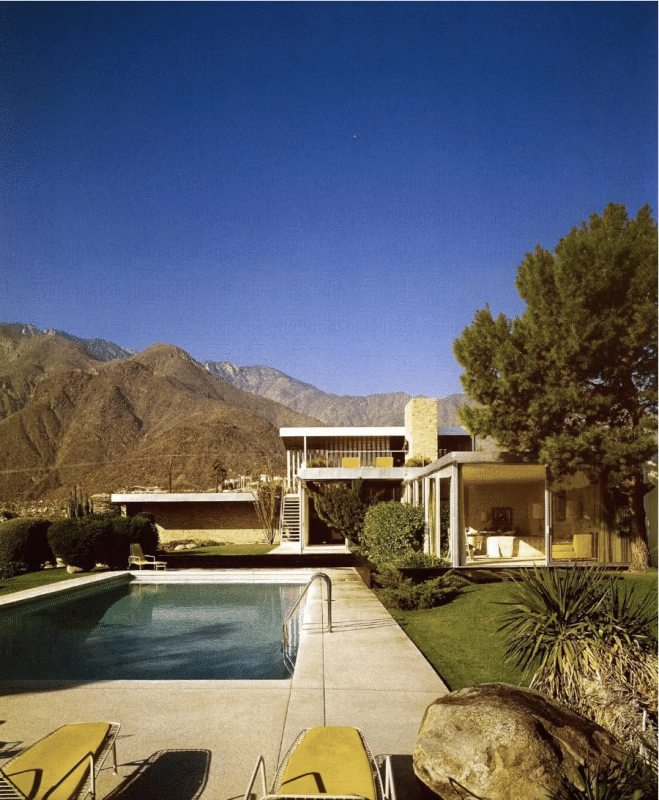

Although local newspapers wrote extensively about both architects, this simply didn’t translate into a national or international profile as what we now call a “Starchitect.” Academics and critics, designers and working architects knew about them, and some championed their best work. Still, this didn’t equate to the near-instant credibility Richard Neutra, say, enjoyed once he graced the cover of TIME on February 3rd, 1947. Though the magazine technically took until the mid-1960s to reach 3 million subscribers, anyone who recalls the era before smart phones will recall that all medical waiting rooms featured copies of TIME right up into the 1990s and even today…rumpled and well-read ones (at least until the smartphone era).

(LIFE, on the other hand soared higher, with an estimated 17 million Americans seeing each issue, what is known as “pass-along” readership, but came to earth earlier. LIFE and its competitors like LOOK crumbled between 1969 and 1972 under the impact of television. Broadcast TV cannibalized their advertising revenue and readership swiftly as color TVs became affordable and ubiquitous).

What Ada Louise Huxtable wrote about Goff in 1970 “…but the East Coast Establishment doesn’t really believe in Goff…he is apt to be dismissed…[as] a designer of outré fantasies” we should see also perfectly applies to that other practitioner of Organic Architecture, John Lautner. The hostility between an aging Frank Lloyd Wright and the American disciples of Gropius and Le Corbusier that developed by the late 1930s had real consequences for those who took their inspiration from Wright rather than Corbu and the Bauhaus.

Goff in fact gave voice to this growing chasm between “Functionalists” and Organic Modernists in that first LIFE coverage. “One of the few US architects whom Frank Lloyd Wright considers creative…[Goff] scorns houses that are ‘boxes with little holes.’ ”

This neglect itself has largely passed into history. The theoretical quarrels at the heart of it are obscure now, even to the well-educated public.

For John Lautner, Posthumous Vindication. For Goff, a Long Slow Fading Away.

Given this transformation, the divergence in name-recognition since 1999 that has emerged between Goff and Lautner in this new century is rather startling. Lautner was virtually unknown outside of southern California after 1980 and before the year 2000 to non-architects. Lautner’s work had been profiled many times in Architectural Digest, Progressive Architecture and other “to the trade” publications from c. 1952 forward. Still, his practice remained small and his income sporadic.

Lautner’s “Chemosphere,” the ‘flying saucer’ house now owned by Benedikt Taschen, was also featured in LIFE magazine (published on August 25th, 1961) and even the Old Gray Lady (“People Who Live in ‘Flying Saucers’ Key Decor to the Landscape“, New York Times, April 29, 1961) — but the headline tells us all. Lautner was another Southern California “eccentric”; everyone in New York knew that Los Angeles, land of the restaurant shaped like a hat, loved kitsch.

Still, East Coast media other than shelter magazines barely took notice of either architect. (The Carling House of 1947 had been featured in a Julius Shulman photo by the New York Times in 1951; but just that).

By 1970, Lautner’s most eye-catching houses were extensively covered by Architectural Digest and similar publications, greater exposure than Goff was ever to receive after 1955 outside of the architecture trade & professional press. But some of Lautner’s great early work remained virtually unknown outside Southern California. His superlative Taylor House, for example, not to forget the Shaffer (1949) and Gantvoort (1947) Houses.

Increasingly, it was filmmakers who fixated on Lautner’s architecture: From the Elrod House’s starring role in Diamonds Are Forever (1971) to Brian De Palma’s Body Double (1984), centered on the voyeurism implicit in the design of the Chemosphere. To, after Lautner’s death, 1998’s The Big Lebowski‘s unforgettable use of the Goldstein-Sheats House’s living room.

Despite the unquestionably considerable media attention John Lautner achieved overall, in the L.A Times and Architectural Digest, it remains baffling: How could the designer of the Elrod House not be world-famous by the late 1970s? How could he not receive a focused profile in TIME, the New York Times or Washington Post, much less the cover of TIME (when it still conferred immense success) before 1990? This curious neglect is today a topic for the historians of design and fodder for Ph’d students in architectural history.

And Goff? Perhaps because his extraordinary houses are scattered about smaller cities in Oklahoma, Missouri, Kansas, and not just near Chicago but sited in smaller cities across Illinois, they simply don’t have the diamond-sharp 21st Century star-power that Lautner’s houses have acquired over the past two decades. Even though the great majority of Goff-designed residences aren’t as radically experimental as the Bavinger or Struckus Houses. The national media attention Goff did receive celebrated his most imaginative work. But such structures baffled many, while marking their maker as almost a visitor from another planet.

Indeed, one of Goff’s masterworks, the 1955 Bavinger House in Norman, Oklahoma was tragically demolished just six years ago. None of Goff’s most impressive houses have sold for several million dollars – while Lautner’s residential designs command ever more extraordinary premiums on the rare occasions they come to market.

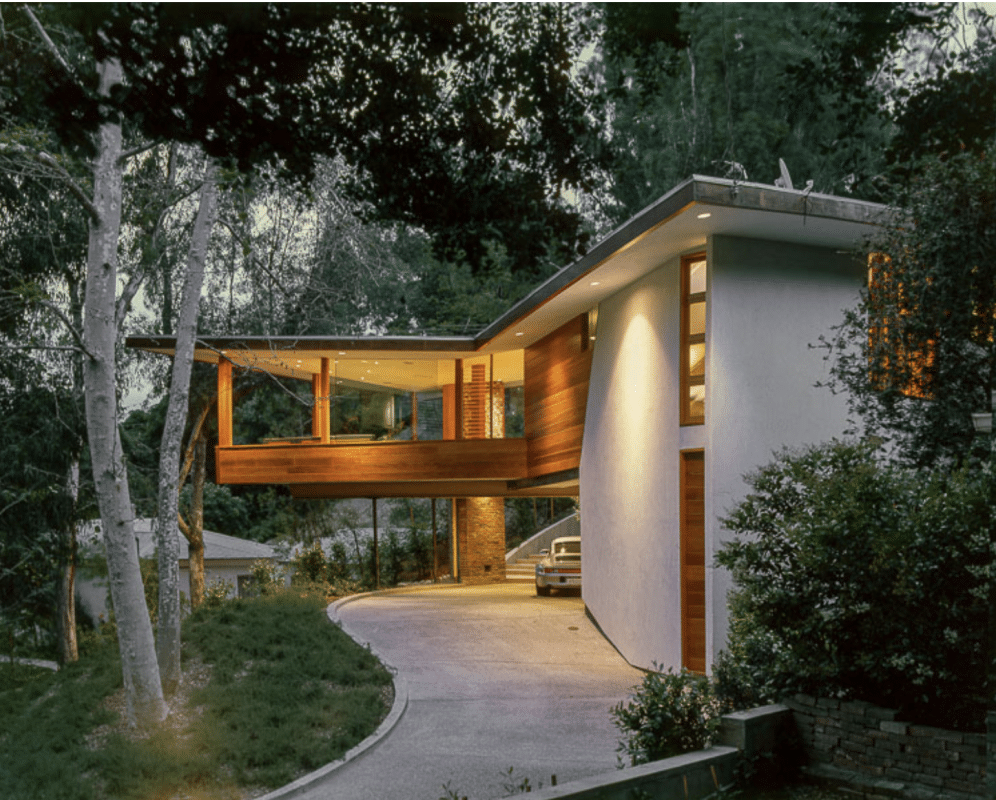

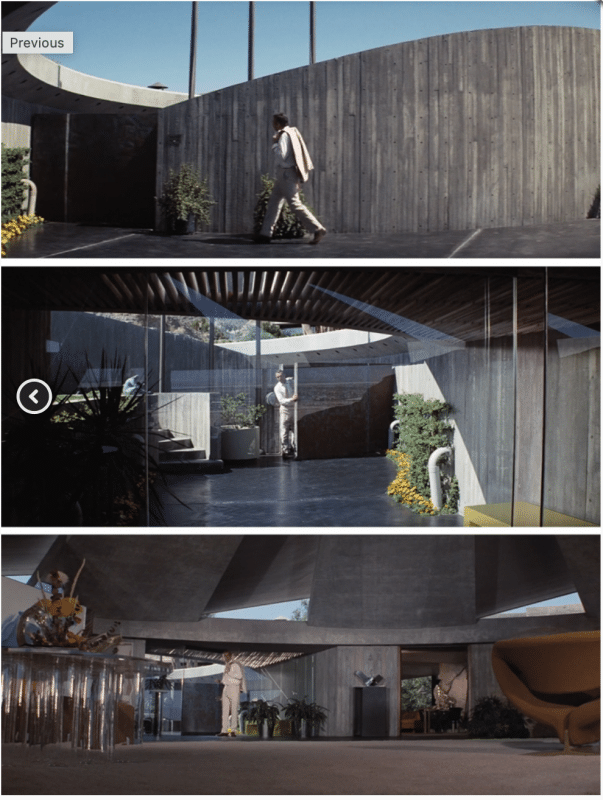

This is shown most clearly by recent news. Crosby Doe listed and sold Lautner’s Garcia House (the “Rainbow House”), as yet unrestored, in 1984 for a then-substantial $439,500. After years of being “quietly available” at a price that most laughed at, the Garcia House sold just this spring for $12,500,000.

While not as celebrated as the Goldstein-Sheats House or the Elrod House, one could see this phenomenal sales price as an inflection point. The Garcia House is slightly more than 2,500 square feet, and though its street-to-street hillside lot affords room for a diamond-shaped pool, it doesn’t have estate-scale acreage. Perhaps this spring was the definitive moment when Lautner’s architecture truly transcended ordinary real estate, soaring into the stratosphere of fine art for good.

In stark contrast, a little more than a year ago a slightly tamer (for Goff!) mid-century house in the suburbs of Kansas City came to market at just under $1 million. And sat on the market…and sat there, and sat there, with repeated price reductions. At last under contract now with a proper architectural specialist listing agent, we thought he might have some interesting things to tell us about how today’s public – outside of New York, Los Angeles, the Bay Area, Seattle and Miami – view inventive mid-century architecture. And how challenging it can be to sell that architecture.

[Our interview with Scott Lane will come in a second Post very soon. Stay tuned!]